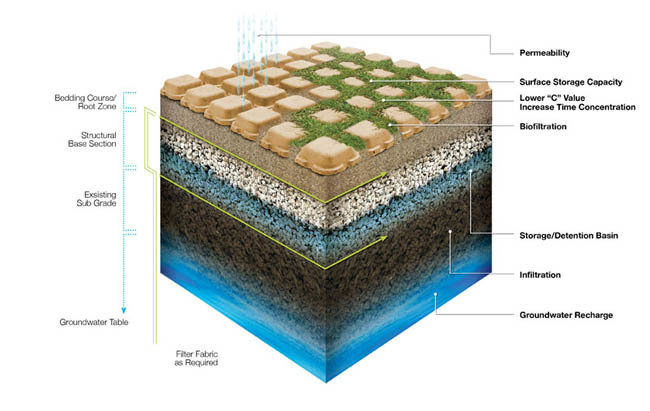

The basic premise of permeable paving systems is simple: Let water drain through pavement instead of across it. It is a boon for designers who advocate environmental responsibility by reducing or eliminating runoff and increasing water quality. However, despite the concept’s seeming simplicity, careless design can create a number of issues that eventually lead to pavement failure.

SmithGroupJJR’s design of the Loyola campus included a sweeping permeable paver walk.

As we, both as a society and a profession, look to “green” how we build, permeable paving has become a popular method of reducing stormwater runoff. There is a challenge, however, in utilizing it properly. Unlike permeable pavements, time-proven traditional engineering always tries to keep water out of the base. Why? Because water can be a powerful force in causing pavement to fail. As a result, we as designers must understand the influences of site conditions—like soil, climate, and rainfall—on the different components in order to ensure we can avoid the danger of introducing water into the base. Let’s take a look at a number of the key issues that might cause it to fail if designed improperly.

Intense Rainfall

Local rainfall patterns affect the necessary infiltration rates of the pavement. Some regions, like the Pacific Northwest, experience relatively low-intensity storm events. Here, choosing pavements with low infiltration rates can be acceptable. Different permeable pavements can provide anywhere from 10 in/hr to over 4000 in/hr of infiltration, but the standard acceptable baseline is 140 in/hr. If a rainfall event exceeds a pavement’s ability to infiltrate, the pavement floods and generates runoff. If, in fact, the goal is to achieve 100% infiltration, the heavier and more prolonged rain events a region receives, the deeper the sub-base needs to be for storage.

(Related Story: Philly Grad Creates Free Cloud-Based Stormwater Modeling Tool)

Poor Soils

Sandy soils are optimal for permeable paving. They drain quickly, reducing the likelihood water will be stored in the base. Often, even in regions with intense rainfall, the sub-base depth can be minimal. However, when permeable paving is sited on clay soils, the sub-base becomes highly important, since the sub-grade becomes easily saturated. Infiltrating water through the base brings up the issue of stability, especially in poor-draining soils. Water can cause the sub-grade and even the base to shift without proper containment. Geotextiles play a key role in the drainage capability and structural integrity of the pavement even though they are typically seen only as barrier to prevent clogging. The specified fabric can make or break the success of the pavement. Some do not allow any drainage, so the base remains permanently inundated—a pretty catastrophic situation! Others wick water horizontally, like a paper towel. These can keep water infiltrating when only one particular part of the sub-grade is inundated. Furthermore, since the sub-grade will frequently be wet, strong fabrics are essential because they can bridge soft spots in the sub-grade and lock the aggregate in place.

This illustration shows basic structural components of a concrete grid paving: paving, bedding, base, sub-base, and drainage fabric (with no underdrain).

(Related Thread: What’s Wrong with This Picture: Episode III – Revenge of the Site)

Cold Climates

Since water is designed to be stored in the sub-base of permeable pavements, frost heave is a serious issue when dealing with freezing temperatures. When combined with poor-draining soils, cold climates pose a very serious risk to their longevity. The key is to make sure water leaves the base as quickly as possible, which requires the use of an underdrain. Underdrains unfortunately lower true infiltration rates. However, without an underdrain, frost will almost certainly cause heaving.

In the end, it is imperative that we, as the designers, understand the complexity behind permeable pavement so that we can design appropriate, functional, and long lasting landscapes instead of simply marking off the sustainability checkbox.

Images via SmithGroupJJR (Photographer: Ken Cobb), Interlocking Concrete Pavement Institute, John Harrison, Soil Retention

Information via Dan Salsinger, Bruce Ferguson, the Center for Water and Watershed Studies, University of Washington and the EPA.

Published in Blog