Author: BimDjSoftech

Contemporary Italian Garden Offers Renewed Inspiration

Contemporary Italian Garden – Private Residence, by Giuseppe Lunardini Landscape Architecture, in Ortonovo (Liguria), Italy. For landscape architects, private residences can often be a chance to showcase their creativity and create spaces that truly reflect not only their clients’ personalities but also their own design aesthetics. For Giuseppe Lunardini, this contemporary Italian garden in the hills of Ortonovo, close to the Mediterranean coast, is an excellent example of how a project can do just that. The owner, a businessman working in the marble sector, wanted that the traditional design of residential gardens be re-thought for his new home, and Lunardini happily obliged. As a designer, who views his firm as a workshop, or laboratory, where experimentation is encouraged and designs are created with close client collaboration, this is exactly the kind of project that Lunardini specializes in.

The masterplan of the private residence garden. Image courtesy of Giuseppe Lunardini Landscape Architecture

Contemporary Italian Garden

To start off, the design team decided that the best approach would be to create a series of outdoor green rooms that would become more natural and nuanced as one moves away from the primary residence. Natural stone, being in sync with the owner’s profession, is found throughout the property and is one of the many ways in which the designer used materials to unify the space.

Photo credit: Andrea Simonetti and Giuseppe Lunardini

Design Features

The final design includes a swimming pool area, an outdoor kitchen, an entrance garden and a parking area. Each space has its own feel but all come together cohesively due to the effective use of plants as structural elements and due to the use of stone.

Photo credit: Andrea Simonetti and Giuseppe Lunardini

The Inspiration Behind The Design

This design approach is an inspiration from Pietro Porcinai, a renowned Twentieth-century Italian landscape architect whose projects featured gardens that were so integrated into their surroundings that they appeared natural and un-designed. “Following Porcinai’s principles and comparing garden elements with architectural ones, I consider bushes as walls, lawns as floors, and trees as columns. So, I always leave all the horizontal surfaces (lawns) free from bushes or trees, which are used to define the green rooms of my gardens,” said Lunardini.

Photo credit: Andrea Simonetti and Giuseppe Lunardini

- Mediterranean Terrace Provides Inspired Living in Italy

- Historical Square Gets a Shocking Makeover!

- New Piazza Design Turns Dead Space into Vibrant Social Space

The most obvious use of plants as structural elements, or walls, can be found in the guest parking area where there are massive shrubs surrounding the white and gray stone floor. These shrubs continue along the road to the orchard and serve as a way to frame the view and lead visitors up the hill to the family parking and the residence.

Photo credit: Andrea Simonetti and Giuseppe Lunardini

Planting Variety

These structural plants can also be found in the surrounding Mediterranean landscape and include local species of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis), Oleander (Nerium oleander), Shrubby germander (Teucrium fruticans), Holly oak (Quercus ilex), Dwarf strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo), Sweet bay (Laurus nobilis), Mediterranean fan palm (Chamaerops humilis), King sago palm (Cycas revoluta), Bird of Paradise (Strelitzia reginae), Agave (Agave Americana), and an area of Olive trees. He also introduced some tree species, including Italian cypress (Cupressus sempervirens), Banana tree (Musa paradisiaca), and Cork oak (Quercus suber) to further anchor the rooms to the surrounding landscape.

Photo credit: Andrea Simonetti and Giuseppe Lunardini

Dynamic Planting

In the rooms that are closer to the house and swimming pool, a softer, more colorful palette of plants was chosen as a way to invite people in and encourage them to linger around. Flowering shrubs like Roses, Oleander and Abelia mixed with perennial Agapanthus were chosen not only for their visual effect but also for their fragrance for these active rooms. Finally, to ensure that the landscape had the natural appearance Lunardini was going for, he also included a variety of grasses, perennials and native shrubs mixed with ornamental plants like Boxwoods and Yews.

The Outdoor Kitchen

In addition to his love of Porcinai, Lunardini also loves contemporary sculpture and always tries to include some sort of sculptural art in his designs. In this case, the outdoor kitchen becomes the art. Lunardini describes the kitchen by saying that, “The most designed area is obviously the outdoor kitchen with its squared CorTen planters and the pergola that continues to the existing portico. I placed it in harmony with this piece of landscape by using natural materials and by embracing it with vegetation.”

Photo credit: Andrea Simonetti and Giuseppe Lunardini

Making Good Use of CorTen Steel

The structural use of CorTen steel can also be found in the pedestrian gate, which is meant for the weather and develop the recognizable patina. This repetition of materials not only helps to unify the site but also provides a natural effect for the man-made structures.

Photo credit: Andrea Simonetti and Giuseppe Lunardini

The Swimming Pool Area

The last room, the swimming pool area, is meant to be an artful representation of a lake situated in a valley. The combination of wood and stone is used to create a structural, yet natural body of water situated among the lush gardens.

Photo credit: Andrea Simonetti and Giuseppe Lunardini

Photo credit: Andrea Simonetti and Giuseppe Lunardini

Using an Infinity Edge

The pool features an infinity edge that allows swimmers to enjoy the spectacular view of the gardens and beyond, while also allowing water to flow over to a gravel area where it is purified. Lunardini describes the voluminous bushes that surround the pool as creating “a perfect continuity with its territory.”

Photo credit: Andrea Simonetti and Giuseppe Lunardini

Full Project Credits For The ASLA Headquarters

Project: Contemporary Italian Garden – Private Residence Design: Giuseppe Lunardini Landscape Architecture Size: 6,200 square meters Location: Ortonovo (Liguria), Italy Firm: Giuseppe Lunardini Landscape Architecture – Lucca (LU) Project team: G. Lunardini, Landscape Architect; G. Sani, Architect; A.M. Varetti, Architect; D. Togneri, Surveyor Photographer: Andrea Simonetti and Giuseppe Lunardini Recommended Reading:

- Urban Design by Alex Krieger

- The Urban Design Handbook: Techniques and Working Methods (Second Edition) by Urban Design Associates

Article by Erin Tharp Return to Homepage

Fiona Stanley Hospital: A Landscape for Healing

Fiona Stanley Hospital, by HASSELL, in Perth, Western Australia. Hospitals are places where people go to heal, so it comes as no surprise that when asked to design the landscape at Fiona Stanley Hospital, the landscape architects at HASSELL sought to create a naturally healing space. Working alongside the other members of the Fiona Stanley Hospital Design Collaboration — Hames Sharley and Silver Thomas Hanley — HASSELL was able to create an outdoor environment that blends with the indoor spaces of the hospital and allows patients to recover and exercise, both indoors and out. The concept behind these seamless transitions and other design initiatives is discussed in the following video. WATCH: Fiona Stanley Hospital

Before design work even began, the collaboration called on an evidence-based health-care designer for advice on how to proceed. Roger Ulrich, a consultant on the hospital’s design, conducted studies showing that green vistas, natural sunlight, and access to natural surroundings all work together to not only improve patient psychological and physical wellbeing but also to reduce the length of stay and the need for pain medication. His study also showed that easily accessible outdoor spaces can also benefit hospital staff seeking a brief respite from their stressful work environment.

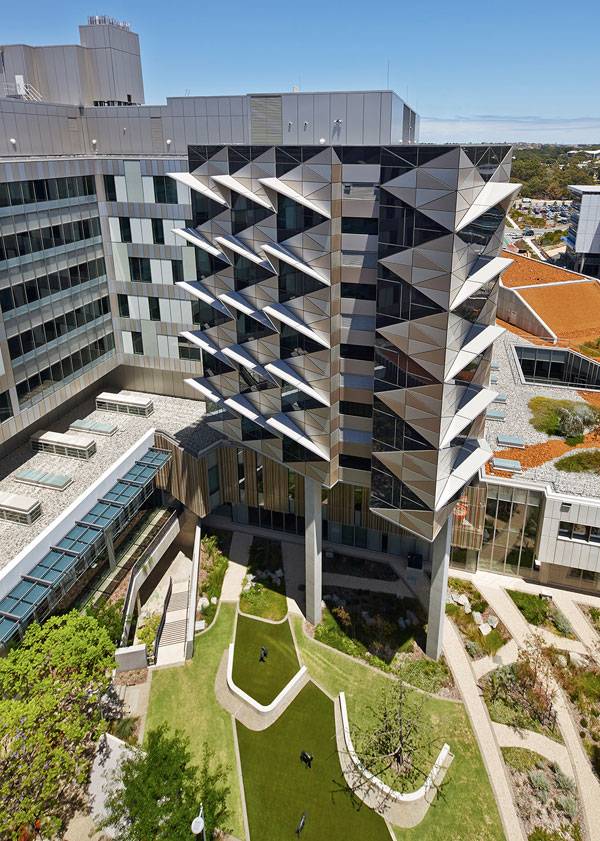

Fiona Stanley Hospital. Photo credit: Peter Bennetts

- 10 Great Projects Showing why Australia are Leaders in Landscape Architecture

- Australia to Lead the World in Green Infrastructure for a Healthier Nation

- The Australian Garden That Everyone’s Talking About!

Fiona Stanley Hospital. Photo credit: Peter Bennetts

Designing for Healing

Located in Perth, Western Australia, the 783-bed hospital was recently awarded the George Temple Poole Award and named the state’s most sustainable project, winning the Wallace Greenham Award for Sustainable Architecture at the 2015 Western Australia Architecture Awards. Judges noted that “The integration of architecture, landscape, and public art is remarkable, creating memorable moments which photographs cannot capture.” This is partly due to the landscape in and around the hospital precinct, which not only reuses the site’s existing flora, but also provides a haven for local wildlife — all while being home to rehabilitation aids throughout its park-like grounds. This can be seen in the following video produced by HASSELL. WATCH: Fiona Stanley Hospital – a healing landscape

Western Australia Architecture Awards judges said the hospital sets the benchmark for other public buildings in Western Australia with its dedication to sustainable design. Brenden Kelly, a principal at HASSELL, responded by saying: “Fiona Stanley Hospital sets a new standard in ‘green’ health-care design for Western Australia. The client and design team took a holistic approach to sustainability for this project, and the scale and number of initiatives we have adopted are unprecedented for a public precinct in Western Australia.”

Fiona Stanley Hospital. Photo credit: Peter Bennetts

- 24,000 msq streetscapes

- 16,500 msq public open space

- 10,000 msq building zone setting spaces and courtyards

- 5,000msp roof gardens

Fiona Stanley Hospital. Photo credit: Peter Bennetts

Planning for Sustainability

To maintain the extensive on-site gardens, the designers realized the site would need an extensive irrigation system, but were hesitant to create a system that would consume so much water. To manage this, a system of swales, a scenic lake, integrated parkland detention areas, and underground infiltration tanks collect, filter, and return storm water to the local aquifers, where the water is then collected to use in the site’s irrigation system.

Fiona Stanley Hospital. Photo credit: Peter Bennetts

The designers also used as many native species of plants as they could to further cut down on extra water needs. More than 2,100 trees and 160,000 shrubs, mostly native, were used to reestablish greenways and connect the site to two surrounding bushland conservation areas.

Fiona Stanley Hospital. Photo credit: Peter Bennetts

Building for Life

Even the façade of the building connects the hospital to the local landscape. The shapes, textures, and colors of the Banksia plant cones that are found throughout surrounding woodlands inspired the repetitious diamond geometry on the building’s facades. Finally, a botanically diverse rooftop garden was designed to be a link for another important species found in the local habitat, the federally protected Carnaby Black Cockatoo. Even the hospital’s namesake, renowned public health researcher Professor Fiona Stanley, is singing the hospital’s praises.

Fiona Stanley Hospital. Photo credit: Peter Bennetts

Fiona Stanley Hospital. Photo credit: Peter Bennetts

Full Project Credits For Fiona Stanley Hospital

Project: Fiona Stanley Hospital Location: Perth, Western Australia Client: Brookfield Multiplex/Government of Western Australia Scale: 320,000 sqm precinct/65,000 sqm planted landscape Year: 2014 Design Team: The Fiona Stanley Hospital Design Collaboration (HASSELL, Hames Sharley, and Silver Thomas Hanley) Landscape Architect: HASSELL Consultants: Roger Ulrich (evidence-based design), Stratagen (environment), O’Brien Harrop Access (accessibility) CADsult (irrigation) Photography: Peter Bennetts Plan/Section: HASSELL Website: www.hassellstudio.com Recommended Reading:

- Urban Design by Alex Krieger

- The Urban Design Handbook: Techniques and Working Methods (Second Edition) by Urban Design Associates

Article by Erin Tharp Return to Homepage

X-TRACK MOTORSPORTS Tatuí – A Racetrack to Help the People

X-TRACK MOTORSPORTS Tatuí, by Eduardo Terra, located near two highways– Castelo Branco (SP 280) and Raposo Tavares (SP-270) — Brazil. For the last four years, Eduardo Terra has been hard at work performing feasibility studies and sports market analysis in order to build a racetrack that will encompass more than 1-million-square-meters (1,000,000 m²) outside the city of São Paulo, Brazil, in the municipality of Tatuí. The project, both large in size and cost, also has a chance to have a large impact on the communities that surround it based on the number of businesses that it will include and the number of jobs it will provide. In addition to the racetrack, the X-TRACK MOTORSPORTS facility will also include condominiums, an exhibition center, a village mall, a hotel, a hospital, a technological center and even a heliport. But the racetrack will definitely take center stage.

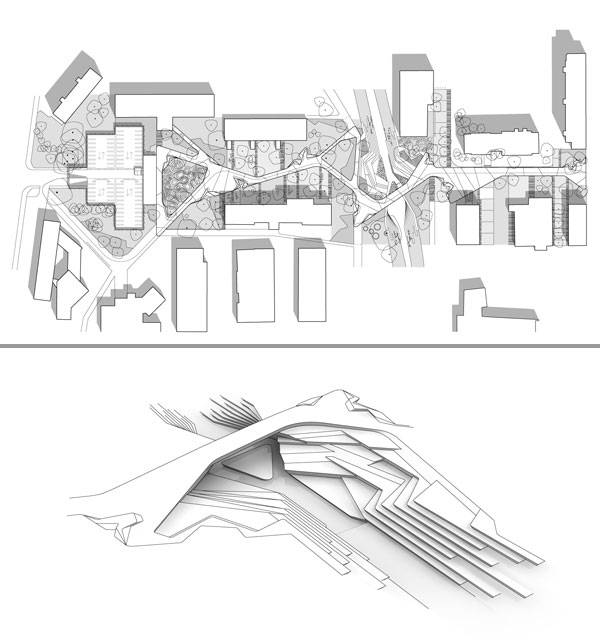

Masterplan of X-TRACK MOTORSPORTS Tatuí. Images courtesy of Eduardo Terra.

X-TRACK MOTORSPORTS

The racetrack will be home to 20 boxes in the pit lane line and 12 stores with 355 square meters of outdoor shopping in the paddock with an additional 32 stores on the ground floor of the pavilion stands. There will be 60 additional boxes, each with two private bathrooms equipped with showers; a kitchen area and a mezzanine for private events as well as two private parking spaces. Designers ensured there would be ample parking by allotting 6,000 parking spaces for cars and 1,000 spaces for motorcycles.

X-TRACK MOTORSPORTS. Image courtesy of Eduardo Terra,

A Race Track With 11 Different Options

To ensure that race fans don’t get bored, the team at Eduardo Terra designed a track with 11 different options and a change of direction at the start. The track is 16 meters wide, with a total length of 5,640 meters. It contains 16 curves, with six to the right and 10 to the left.

How Does This Project Benefit The Locals?

It is this focus on the racetrack that led the other enterprises to sign on to the project. Through their participation, the project is expected to create 400 direct jobs and 5,000 indirect, which will have a huge impact on the local economy. Local citizens will also benefit, as X-TRACK MOTORSPORTS plans on distributing a ticket to every public education student for any event that is held at the track. Another long lasting effect the project hopes to have is the educational aspect it brings to the area.

X-TRACK MOTORSPORTS. Image courtesy of Eduardo Terra

An Investment in The Future

The on-site technological center will also serve as an educational center where future mechanics, pilots, and trainers will receive valuable instruction that will one day enable them to get well-paying jobs in the industry. Finally, the project hopes to garner international attention by hosting national races that are already established in Brazil, including the Brazilian Motorcycling Federation motorcycling championships in Brazil: Moto GP 1000 – Brazilian Championship motorcycling; Superbike Series; and the Brazilian Championship Supermoto, Motocross, Cross Country Rally, Enduro Regular and Enduro FIM.

X-TRACK MOTORSPORTS. Image courtesy of Eduardo Terra

Greening up the Space and Connecting it to the Surroundings

Thus far, it might sound as if the project is going to be a concrete jungle filled with bright lights, cars and speeding motorcycles, but that would be a very incorrect assessment. In fact, the designers have incorporated as much green space as the site would allow for and took advantage of the breathtaking views of the surrounding Mantiqueira Mountain range. They installed groves of lush palm trees and other native trees found in Brazil to shade pedestrians on the ample sidewalks found throughout the development.

X-TRACK MOTORSPORTS. Image courtesy of Eduardo Terra

X-TRACK MOTORSPORTS. Image courtesy of Eduardo Terra

Design Considerations

By using mostly low-lying buildings, the designers were able to flood the entire project with natural light, which is necessary for the tropical plantings incorporated throughout. The project also keeps a low profile that doesn’t interfere too much with the surrounding farmland. Designers also took into account the noise that would be generated from the races and situated the development far enough from the congestion of the city to ensure that it would not become an issue. But what does all of this have to do with landscape architecture? Quite simply it’s the socio-economic impacts that the project will bring to this region. As stated above, not only will the project provide much-needed jobs in a Brazilian economy suffering from growing unemployment but it will also provide much needed advanced education for the people and much-needed tourism money that the local economy can then filter back to it’s people.

X-TRACK MOTORSPORTS. Image courtesy of Eduardo Terra

X-TRACK MOTORSPORTS. Image courtesy of Eduardo Terra

Full Project Credits For X-TRACK MOTORSPORTS

Project: X-TRACK MOTORSPORTS Location: Tatuí, near two highways– Castelo Branco (SP 280) and Raposo Tavares (SP-270) — Brazil Architect: Eduardo Terra Project Managers: Eduardo Terra and Arnaldo Yansen Cost: R$171.512.079,10 Size of Racetrack: 1.085.814,82 m2 Website: www.eduterra.com.br Recommended Reading:

- Urban Design by Alex Krieger

- The Urban Design Handbook: Techniques and Working Methods (Second Edition) by Urban Design Associates

Article by Erin Tharp Return to Homepage

Quzhou Luming Park Proves that Natural Processes Offer the Most Sustainable Solutions

Quzhou Luming Park by Turenscape, in Quzhou, Zhejiang, China. A sea of color greets visitors when they enter the new Quzhou Luming Park, and it is a color palette that changes with the seasons. Located along the west bank of Shiliang Creek west of the new district of Quzhou, the 31.3-hectare park is a place where agriculture meets healthy living. and the two combine to produce a spot that attracts people from all walks of life. Home to more than 2.5 million people, Quzhou features picturesque landscapes and abundant natural resources, both of which helped the city to be named a National Eco-Model City, National Garden City and to receive the title of Excellent National Tourism City. It was with this in mind that first-level design institute Turenscape set out to design the district’s newest park and tourist attraction.

Quzhou Luming Park. Photos courtesy of Turenscape

Quzhou Luming Park

Knowing that Quzhou has a goal of becoming the green base for the marine economy of China’s Zhejiang province and for transforming the city into a place filled with culture, ecology, and dynamic entrepreneurship, Turenscape designed a park that represents all that Quzhou is attempting to become. More Incredible Projects by Turenscape:

- Turenscape Design Outstanding River Park

- How the Extraordinary Qunli Stormwater Park got Listed as a National Wetland Park

- Fantastic River Park Unveils the Value of the Natural Landscape

Quzhou Luming Park. Photos courtesy of Turenscape

Quzhou Luming Park. Photos courtesy of Turenscape

Quzhou Luming Park. Photos courtesy of Turenscape

Quzhou Luming Park. Photos courtesy of Turenscape.

Quzhou Luming Park. Photos courtesy of Turenscape.

Quzhou Luming Park. Photos courtesy of Turenscape.

Quzhou Luming Park. Photos courtesy of Turenscape

Quzhou Luming Park. Photos courtesy of Turenscape

Quzhou Luming Park. Photos courtesy of Turenscape

Quzhou Luming Park. Photos courtesy of Turenscape.

Quzhou Luming Park. Photos courtesy of Turenscape

Quzhou Luming Park. Photos courtesy of Turenscape.

Full Project Credits For Quzhou Luming Park

Project: Quzhou Luming Park Location: Quzhou, Zhejiang, China Project Size: 31 hectares Landscape Architect: Turenscape Date of Design: February 2013 Date of Completion: 2015-2017 Client/ Owner: Quzhou Infrastructure Investment Pte. Ltd. Website: www.turenscape.com Recommended Reading:

- Urban Design by Alex Krieger

- The Urban Design Handbook: Techniques and Working Methods (Second Edition) by Urban Design Associates

Article by Erin Tharp Return to Homepage

How Velenje Promenada Brought Light and Sunshine Back to the City

Velenje City Center Pedestrian Zone Promenada, by ENOTA, in Velenje, Slovenia. As a central axis to the fifth-largest town in Slovenia, the Velenje “Promenada” is quickly becoming an important space in the young garden city. Built in the 1950s on the Modernist’s ideal, the city is one of only a few modernistic cities in Europe, and this latest installation by ENOTA continues to follow these ideals and is representative of the city’s commitment to revitalizing the city center. After a fire destroyed the original city in 1801, it seemed that the remaining 364 inhabitants might be the last. But by the end of the 19th century, the town began to have hopes of revitalization after a coal mine opened on the city’s outskirts. But it wasn’t until after 1950, when there was an increased demand for coal, that an actual, modern town was needed. THE DIRECTOR OF RUDNIK VELENJE, Mr. Nestl Žgank assembled a team of design engineers for the Slovenija project, Ljubljana, led by architect Janez Trenz, who started developing plans for a modern town that would accommodate approximately 30,000 residents. Žgank’s motto of “… the dwelling places of miners, who spend half of the day underground, should be filled with light and sunshine…” resulted in both a modern and contemporary town, with buildings situated in large, green areas, known as a town-in-a-park.

Aerial view of Velenje City Center Pedestrian Zone Promenada. Photo credit: Branko & Nik NavrsÌŒnik)

Velenje City Center Pedestrian Zone Promenada

Transforming a Road into an Intimate Path

It was with this in mind that designers at ENOTA began the process of transforming an existing promenade that was created almost 30 years ago when a road was closed. Despite a repaving of the area, it still looked very much like a road, and designers were tasked with making it fit into the modern character of the city, allow for expansion, supply the city with missing programs, and thus bring culture back to the town center.

Velenje City Center Pedestrian Zone Promenada. Photo credit: Miran Kambič

Velenje City Center Pedestrian Zone Promenada. Images courtesy of ENOTA

- Urban Design by Alex Krieger

- The Urban Design Handbook: Techniques and Working Methods (Second Edition) by Urban Design Associates

Velenje City Center Pedestrian Zone Promenada. Photo credit: Miran Kambič

Velenje City Center Pedestrian Zone Promenada. Photo credit: Miran Kambič

Embracing the River

Before the Promenada was redone, a wide bridge crossed over the river, which eventually flowed out of sight somewhere beneath it. The designers realized that most passersby probably didn’t even notice the river when on the bridge, and knew that it should be the focal point of the city. See More Pedestrian Inspired Designs:

- Place Lazare Goujon is Once Again Dedicated to Pedestrians

- The ChonGae Canal Turns an Auto-Centric Zone into a Pedestrian Haven

- Top 10 Pedestrian Bridges

Velenje City Center Pedestrian Zone Promenada. Photo credit: Miran Kambič

Velenje City Center Pedestrian Zone Promenada. Photo credit: Miran Kambič

Velenje City Center Pedestrian Zone Promenada. Photo credit: Miran Kambič

Velenje City Center Pedestrian Zone Promenada. Photo credit: Miran Kambič

Taking a Page from History

Researching not only the site but also the history of the area is what led to the success of this transformation. The city of Velenje has a colorful and varied history, but also a very straightforward design intention based on the political views of its residents.

Pre-concert playground. Photo credit: Roman Bor.

Velenje City Center Pedestrian Zone Promenada. Photo credit: Miran Kambič

Velenje City Center Pedestrian Zone Promenada. Photo credit: Miran Kambič

Velenje City Center Pedestrian Zone Promenada. Photo credit: Miran Kambič

Full Project Credits For Velenje City Center Pedestrian Zone Promenada

Project: Velenje City Center Pedestrian Zone Promenada Dates: 2012-2014 Size: 17,020 square meters Budget: 2,700,000 EUR Client: Velenje Municipality Location: Velenje, Slovenia Architect: ENOTA Project Team: Dean Lah, Milan Tomac, Tjaž Bauer, Andrej Oblak, Polona Ruparčič, Nuša Završnik Šilec, Alja Černe, Nebojša Vertovšek Structural Engineering: Elea iC, Nom biro Electrical Planning: Elsing Photos: Miran Kambič Recommended Reading:

- Urban Design by Alex Krieger

- The Urban Design Handbook: Techniques and Working Methods (Second Edition) by Urban Design Associates

Article by Erin Tharp Return to Homepage

Australia to Lead the World in Green Infrastructure for a Healthier Nation

Australian Institute of Landscape Architects Calls on Federal Government to Lead the World in Green Infrastructure for a Healthier Nation. The Australian Institute of Landscape Architects is on a mission to help change the landscape of an entire continent in order to improve the health of its citizens. To do this, they are urging the federal government to come forward and acknowledge that the urban landscape of Australia is in need of improvement. They hope these improvements will come in the form of green infrastructure. To start their mission, AILA developed a National Green Infrastructure Strategy with four key recommendations and has submitted it to Australia’s 15-Year Infrastructure Plan for Australia. What is it, though, that has led AILA to push this plan? Surprisingly, it is adult obesity, which is defined by the World Obesity organization as a medical condition in which a person has excess body weight in the form of fat that can lead to severe health problems. According to the Australia Institute of Health and Welfare, Australia is one of the most obese places in the world, with 60 percent of Australian adults considered overweight or obese. In fact, the institute predicts that these numbers will continue to grow, and that by 2025 close to 80 percent of Australian adults will be obese. This is why AILA is urging the federal government to create tangible solutions for this growing problem.

The High Line New York. Photo credit: © Urban Land Institute (Flickr). Image via 15 Year Infrastructure plan for Australia PDF. Permission for use granted by a representative of OPF Consulting.

Making Green Spaces a Priority

“The government (has) the opportunity now to reprioritize outdoor spaces like parks, streetscapes, and public precincts to support healthier modes of transport that enable our population to be more active,” said AILA CEO Shahana McKenzie. “Creating cities that encourage people to get outdoors and connect with their community are essential preventative health measures and can have a real impact in reducing escalating health-care costs,” she said. AILA cites research from a 2005 British Medical Journal entry, “Graffiti, Greenery, and Obesity in Adults: Secondary Analysis of European Cross Sectional Survey”, that shows that the quality of a local urban environment can hugely impact a person’s activity levels. The study went on to show that in cities with more greenery, citizens are three times more physically active and the likelihood of being obese is actually 40 percent less. See More Activity in Australia:

- 10 Great Projects Showing why Australia are Leaders in Landscape Architecture

- The Australian Garden That Everyone’s Talking About!

- How Pirrama Park Saved Sydney’s Harbor from Residential Development

Australian Garden; photo credit: John Gollings

Recommendations

To help cities accomplish this goal, AILA came up with four strategic recommendations: 1. A National Green Infrastructure Strategy from the federal government to provide guidance on how infrastructure projects can be a catalyst for enhanced landscape outcomes through green infrastructure investment. The strategy will include a policy statement to articulate the government’s position on infrastructure investment and investment action areas.

Paddington Reservoir Gardens, joint winner of the 2009 Australia Award For Urban Design.

By Tonkin Zulaikha Greer Architects and James Maher Delaney Design. Image Courtesy of City of Sydney. Image via 15 Year Infrastructure plan for Australia PDF. Permission for use granted by a representative of OPF Consulting.

A Luxurious Example

Saffire is a luxury eco-tourism resort overlooking Tasmania’s Freycinet Peninsula. Led by landscape architect Jerry de Gryse, the team focused on sustainable design principles that are similar to those later developed by AILA. They include: keeping healthy sites healthy; healing injured sites; favoring living, flexible materials; respecting the waters of life; paving less; considering origin and fate of materials; knowing the cost of energy over time; celebrating light, respecting darkness; quietly defending silence; and maintaining to sustain.

SITES at Work

Which cities in Australia will receive the first makeovers? Unfortunately, the problems are too widespread to make the choice simple. “The challenges government (is) facing in relation to health exist in different ways in all parts of Australia. The creation of high-quality outdoor spaces has the benefit of addressing both physical and mental health issues. Each city needs its own strategies to address local challenges,” Frisby said. Thankfully, both state and local governments are excited to accelerate green infrastructure opportunities at the project-development level, and national leadership from Infrastructure Australia will help municipalities receive even more federally funded infrastructure investments. As the growing national advocacy body representing 2,500 active and engaged landscape architects in Australia, AILA is at the forefront of this movement. It stresses that these recommendations are both strategic and collaborative and will hopefully add value to existing practices while creating even more opportunity to improve Australian infrastructure. AILA is encouraging Infrastructure Australia to implement a Project Briefing Guide for Integrating Landscape through Infrastructure Development in the short term (one to two years), as it has the ability to influence project outcomes quickly with no major structural change to existing practices. A concise summary of the group’s goals can be found in the 15-Year Infrastructure Plan for Australia. How has green infrastructure had an impact on your life? Article by Erin Tharp Recommended Reading:

- Designing the Sustainable Site: Integrated Design Strategies for Small Scale Sites and Residential Landscapes by Heather L. Venhaus

- Lifelong Landscape Design by Hugh Dargan

Return to Homepage

How NEO Bankside Became an Unexpected Urban Site for the Birds and the Bees

NEO Bankside, by Gillespies, in London, United Kingdom. Lush native plantings, an orchard of fruit trees, and a thriving beehive are all things one might expect to find around a country home, but how about in a former industrial area in a bustling city? Well, that’s exactly what one will find when visiting the luxury residential development NEO Bankside, located adjacent to London’s Tate Modern, a modern and contemporary art gallery. More than 200 residential apartments housed in a set of contemporary, hexagonal buildings that border the River Thames surround these lush and sustainable gardens designed by London-based landscape architects Gillespies. The buildings, designed by Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, are unique in their external bracing system, which distinguishes them from other buildings in the area. While modern and sleek in nature, the buildings fit in perfectly with the lush, delicate landscape.

Raised planting beds at NEO Bankside. Photo credit: Jason Gairn

NEO Bankside

The designers knew from the start that the area outside the buildings would need to serve two purposes. First, it would need to accommodate passersby going to and from the Tate Modern, one of the busiest museums in the world. Second, it would need to accommodate the NEO Bankside residents. The designers did this by first creating a large public realm at ground level, where groves of alder and birch trees lead visitors from the Tate Modern’s riverside gardens on to Southwark Street. The groves are surrounded by delicate plantings and lawns shaded by larger forest trees that took their inspiration from native woodlands and flow all the way up to the footprint of the buildings.

NEO Bankside, by Gillespies. Photo credit: Jason Gairn

Contrasting Textures Enable a Strong Design

While soft plantings might seem in contrast with the hard lines of the buildings, the effect is in fact complementary. The plantings actually help to situate the buildings in the landscape and offer residents a quiet retreat from the surrounding city. Related Articles:

- Copenhagen’s First Climate Resilient Neighborhood

- 5 Best Ways to Increase Biodiversity in Urban Landscapes

- The Global Collapse in Bee Populations – What You Need to Know!

Stone for paths is cut sharply to echo the precision of the architecture. Photo credit: Jason Gairn

Providing A Micro-Climate

These outdoor spaces also provide residents with their very own micro-climate in an otherwise bustling urban setting. Gillespies’ design specifically called for maximum privacy in the private residents’ gardens. They did this by separating these private spaces from the public routes with a series of heavily planted berms, pebble-lined moats, and narrow walkways. The berms, while separating the private and public spaces, also help the north-south flow of pedestrian traffic and are a reflection of the landscape found at the neighboring museum, which helps connect the two sites.

Fractured paving and deliberately mannered planting provide interesting patterns and create an oriental feel. Photo credit: Jason Gairn

How Did They Create Such a Hign Level of Biodiversity?

All of the gardens have a high level of biodiversity, thanks to Growth Industry, a planting consultant subcontracted out by Gillespies for this purpose. This biodiversity is found in everything from the large tracts of native trees to the banks of flowers, and it is all pollinated by bees housed in hives located in the gardens. This, in turn, helps to protect the bees, which are a threatened species. To create a truly diverse and thriving space, the designers even went so far as to include plants that would provide seeds and nesting material to encourage wildlife in the gardens.

Planting has been designed to provide colour and interest throughout the year. Photo credit: Jason Gairn

Gillespies worked with specialist Growth Industry to test and develop the landscaping. Photo credit: Jason Gairn

Attracting insects was a consideration when choosing plants. Photo credit: Jason Gairn

Encouraging Activity in the Space

In an effort to encourage the residents to actually interact with the garden space, the designers included an active fruit orchard and herb garden, providing residents with access to fresh produce. These spaces also add color and fragrance to the gardens, making them more dimensional and sensory oriented.

Designed and Built to Last

Gillespies wasn’t finished yet, though. The designers also carefully selected each and every material used in the space, with long-term performance in mind. They wanted to ensure that each element was not only suitable for the space, but also would limit the impact on the overall environment and stand the test of time.

NEO Bankside, by Gillespies. Photo credit: Jason Gairn

The Power of Having a Multi-Disciplined Design Approach

Finally, Gillespies worked with Hoare Lea engineers to create a rainwater-harvesting system for irrigation. The plan calls for this to be a central tenet of the basement construction, where water-retention reservoirs were laid over the structural slab so that there would always be a reserve of water to maintain soil saturation while limiting the amount of irrigation required. This reserve supplements the irrigation system and limits the use of main water use. All of these factors add up to create a welcoming space for NEO Bankside residents, but they also combine to create a sustainable, functional site, which is an integral part of the design approach at Gillespies.

View of the landscaping from above. Photo credit: Jason Gairn

NEO Bankside, by Gillespies. Photo credit: Jason Gairn

Multi-Award Winning Design

The landscape design has received numerous awards since it was installed, including the Riba National Award in 2015, The Riba London Regional Award in 2015, a 2013 Landscape Institute Award, a 2013 Sunday Times British Homes Award, a 2012 International Property Award, a 2012 New Homes and Gardens Award, a 2012 Evening Standard New Homes Award, and a 2012 RESI Award.

When Sustainability Stops Being a Buzzword and Starts Being the Foundation of a Great Design

Sustainability may be the buzzword of the moment and many projects may claim to achieve it, but it is projects like this one that are truly raising the bar for landscape design. From the use of native plantings to the inclusion of edibles and wildlife, this project goes above and beyond what is expected in terms of sustainability. After all, when was the last time you visited a site where beehives were designed and integrated into an urban project?

Beehives are managed by the London Beekeepers Association. Photo credit: Jason Gairn

NEO Bankside, by Gillespies. Photo credit: Jason Gairn

Full Project Credits For NEO Bankside

Project: NEO Bankside Client: Native Land and Grosvenor Total Area: 7,700 square meters Total Landscape Area: 5,794 square meters Location: Hopton Street, London, SE1 9JT, United Kingdom Design Team: Gillespies, Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, Growth Industry, Hoare Lea, Carillion, Frosts Landscape Completion: 2012 Photographer: Jason Gairn Recommended Reading:

- Urban Design by Alex Krieger

- The Urban Design Handbook: Techniques and Working Methods (Second Edition) by Urban Design Associates

Article by Erin Tharp Return to Homepage

Why Designing For Children is Vital to The Future of Landscape Architecture

We explore the idea that ultimately all public spaces, should be designed with children in mind. Unless a playground is being designed or codes are being reviewed, most landscape architects don’t usually stop to think about how their spaces will be perceived and used by children. But maybe we should? After all, children are future adults and what they believe and do while they are growing up are inevitably the things that will shape the future for not only them but for landscape architecture and us as well. I became pregnant in my second semester of grad school while studying landscape architecture and after having my child and returning to school I suddenly found myself in opposition with many of my classmates and professors over my design choices. All of a sudden every space I saw suddenly was filled with children and all I could think of was how could it be made better for them? No matter how much criticism I received from my professors I was constantly trying to create spaces that were child-friendly and attractive to young families, like myself.

Designing For Children With Child-Friendly Landscape Architecture

One such place that does just this is the Circle in Normal, Illinois. Granted, this space is adjacent to the Children’s Discovery Museum, but it is not a playground, not in the traditional sense anyway. Instead designers included large grassy areas for free play and an educational storm water public fountain. Adults also use both of these but the point here is that children can safely use them right alongside the adults.

While spaces like the Circle still inspire me, I will admit that five years later some of this intense focus on designing just for children has worn off, but I still find myself searching my sites for child hazards and asking my clients if children will ever be using the space.An Interjection From the United Nations

But maybe this isn’t as bad as a certain professor made it out to be in one of my more painful reviews? Maybe there is validity in designing spaces, especially public spaces with children in mind. In fact, it would seem that the United Nations (UN) would agree with me. In 1989, the UN General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) to address the lack of representation by children and most importantly it gives children the right to have their voices heard in all matters affecting them. Since its implementation many cities have joined the child bandwagon and have begun to support the child-friendly cities (CFCs) movement.

A city design to be child-friendly at Citygarden. Photo credit: Cameron Rodman

A landscape acting as an example in our article about designing crime our of landscape architecture. Plaza de la Luna by Brut Deluxe and Ben Busche Architects.

Attracting Families is Vital to The Survival of a City

In cities like Detroit, Michigan attracting families back to the downtown area is vital for the survival of the city and here, Campus Martius Park is doing just that. Here, programs such as ice skating and outdoor movies are geared towards families, but the park also has elements that are attractive to people of all ages like bocce ball courts and wireless internet.

“Picture of the skating rink at Campus Martius Park in Downtown Detroit during Super Bowl XL in February 2006” by MJCdetroit. Licensed under GNU Free Documentation License via Wikimedia Commons

If Women and Their Children Feel Safe, Everyone Feels Safe

Since it is located in the center of the central business district it certainly wasn’t designed just for kids but designers were definitely aware of the fact that if women will bring their children alone then the park will be viewed as safe and will be successful.

While not designed specifically for children, it is a great place for them. Sunken garden at Habima Square. Photography Credits Go To Eran Karu

How do we do this?

We design outdoor spaces and cities that encourage children to explore and spaces where parents feel confident letting their child play unaccompanied. Both of these things can help a child to develop confidence, build knowledge and maybe even create a sense of pride in their surroundings. And who wouldn’t want to live in a city where a child could safely ride their bike to school? This image portrays a city that is perceived as both safe and clean, which further promotes positive childhood experiences. But how do we do this? There are certain steps that we can take to help cities transform themselves into these child-friendly utopias. We can help municipalities with storm water management, we can design streets that are pedestrian friendly, we can encourage the use of bikes and trails, and we can green up their urban environments.

Pedestrian friendly street. “Creative Commons BIG – Bjarke Ingels Group – SUK – Superkilen Park, Copenhagen, Denmark”. Source Forgemind ArchiMedia, licensed under CC 2.0

WATCH: Downtown Bellingham Wa Things To Do

All of these elements add up to create an area that is very attractive to families while also benefitting the local economy, decreasing crime, and making an area more sustainable. Without these sustainable initiatives, children would not be inadvertently exposed to all of the great things that landscape architects do, not only for them but also for their world. It is this idea that hopefully will promote these children to continue the quest of sustainability and maybe, just maybe their childhood experiences will encourage them to go out and create an even better world for their children. And, landscape architecture will inevitably be at the center of the movement. Now, go out and about in your own town or city and take a walk. Are there spaces, other than playgrounds, that you would deem as “child-friendly” and that were designed with the future in mind? Finally, was a landscape architect involved in creating it? Recommended Reading

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

Article by Erin Tharp

Return to Homepage Featured image: “BIG – Bjarke Ingels Group – SUK – Superkilen Park – Photo 0003.jpg” by 準建築人手札網站 Forgemind ArchiMedia. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 via Commons. via Flickr

World Class Example of Community Driven Design at Park Groot Schijn

Park Groot Schijn, Maxwan architects + urbanists, in Antwerp, Belgium. The Park Groot Schijn is an excellent example of how collaborations between local residents and designers can yield beneficial results for everyone involved. A group of designers including Maxwan, Karres & Brands, and Ten Ten worked with residents of both Antwerp and the District of Deurne to create a masterplan that encompasses a wide range of activities and programs that benefit both the people using the space and the environment. The first phase to be built, a 6.5-hectare park, is centered among highways and two small rivers that help to define the space and also helped to determine its overall shape and design. When Maxwan and Ten Ten first visited the phase one site they found it was home to large native woodlands and the meandering Koude Beek. During the planning phase designers served as mediators to reach a compromise between the need to preserve this natural beauty, what residents were asking for,and the governmental regulations.

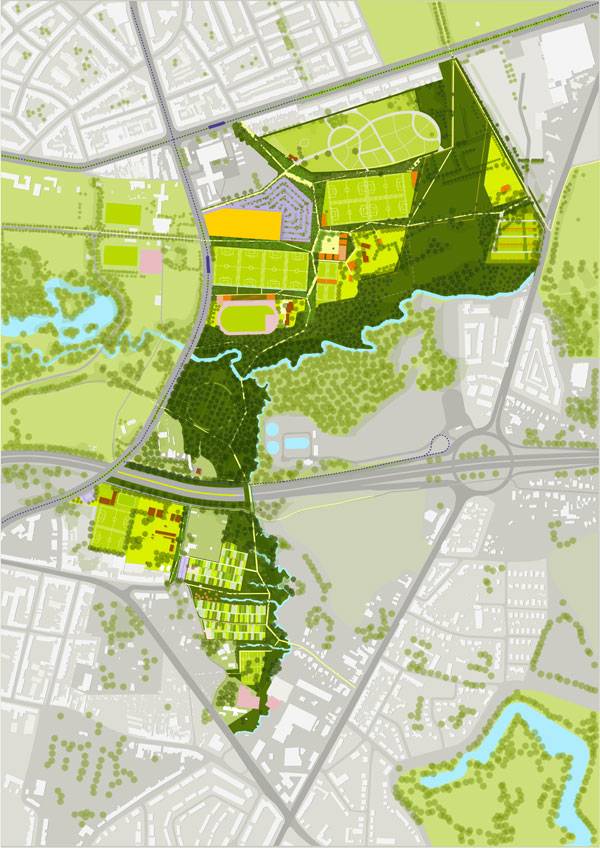

Masterplan of Park Groot Schijn. Image courtesy of Maxwan architects + urbanists

Park Groot Schijn

To accomplish this designers separated the park into joints (green areas) and rooms. The joints, or framework, essentially represent the paths and natural areas, or grasslands, which maintained their natural features and diverse plant species of native grasses and flowers.

Render of Park Groot Schijn. Image courtesy of Maxwan architects + urbanists

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

Park Groot Schijn. Image courtesy of Maxwan architects + urbanists

Inside the Rooms

These natural areas are separated from the rooms by fragmented woodlands, which designers intentionally left. Inside the various rooms one can find a wide variety of programs and functions, including sports, areas for children or dogs, an active caravan park and the allotments, or community gardens. Each room is fully equipped for its specific activity and were carefully placed so as not to interfere with the overall integrity of the park.

Park Groot Schijn. Image courtesy of Maxwan architects + urbanists

Listening to What the Residents Want

During the programming phase designers discovered early on the need for sports to be brought back to the area. Representatives from Deurne voiced the need to make the area a sports district but residents were also sensitive to the natural beauty of the land.

Park Groot Schijn. Image courtesy of Maxwan architects + urbanists

Building the Site in Stages

Due to the overall size of the entire finished park, it was designed and is being built in phases. The first phase, which includes the original 6.5-hectares is complete and is located to the south of the E313 highway. This phase includes the refurbished 172 community gardens and an additional 30 gardens and parking for 50 cars. Designers also made modifications to the existing terrain by adding four wadis, or dry channels, to deal with the water management on site.

Park Groot Schijn. Image courtesy of Maxwan architects + urbanists

Flemish Spatial Planning Award

The Masterplan for the Ruggeveld-Boterlaar-Silsburg was awarded the Flemish Spatial Planning Award for its innovation and excitement in the field of spatial planning. This award was also given due to the collaboration aspect of the project. In the end, over 40 groups actively participated in a total of 19 meetings where the design was discussed and revised at each one, a true feat in and of itself.

Park Groot Schijn. Image courtesy of Maxwan architects + urbanists

376 Entries to Name the Park

As a final nod to community involvement the design committee held a competition to name the park. They received 376 entries and on September 11, 2011 announced the chosen name, Park Groot Schijn, is in reference to the Schijn rivulet that runs through the park. This park shows that by consulting with the actual users of a space that community needs can truly be met without sacrificing the environment. But, with all of this collaboration was the actual design aspect sacrificed to create a space that was functional but not necessarily visually stunning?

Full Project Credits for Park Groot Schijn

Project Name: Park Groot Schijn Program: Landscape, park, community gardens, parking Location: South of the E313 highway, Antwerp, Belgium Size: 6.5 hectares Collaborators: Maxwan architects + urbanists, 1010 architecture+urban design, Antea Group Client: AG Stadsplanning Antwerpen Partner in Charge: Rients Dijkstra Team Leader: Martijn Anhalt Construction: 2011 – 2013 Project leader: Steven Geeraert. Team: Rene Heijne, Aleksandar Hrib, Harm te Velde Recommended Reading

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

Article by Erin Tharp

7 Top Pocket Parks: Small Spaces With a Huge Impact

We take a closer look at 7 top pocket parks that have a lot to offer. Pocket parks (also called mini-parks) are small oases in urban settings that are usually the size of only one or two lots. These small spaces are usually classified as neighborhood parks, and therefore need to be designed with many activities in mind. They can be used as play areas, for taking lunch breaks, or even for small events. Most importantly, they should be a place of quiet refuge and escape from the busy city life surrounding them. The most successful pocket parks achieve a balance between this quiet escape and active meeting and play. These are the ones that have made our list of the “Top 7 Pocket Parks” (in no particular order).

Top Pocket Parks

WATCH: The beauty of pocket parks

1. Greenacre Park, Midtown Manhattan, New York City

Greenacre Park is home to a waterfall, honey locust trees, and moveable tables and chairs. Designed by Sasaki, Dawson, DeMay Associates — with Masao Kinoshita as lead designer — the pocket park opened in 1971 after being privately funded by Abby Rockefeller Mauze’s Greenacre Foundation, which continues to maintain it. At a mere 60 feet by 120 feet, the space feels much larger than it actually is due to the trellis-covered terrace that separates it from the street. A fountain and runnel lead visitors into the space, where they are greeted by a 25-foot-high cascading waterfall open to the sky and surrounded by evergreens.

2. Place Dauphine, 1st Arrondissement, Paris, France

Henri IV built this square more than 400 years ago as a tribute to his son, Louis XIII, and it still remains one of the most popular places to visit when traveling to the City of Light. The park is a triangle situated among quiet Parisian streets and offers views of the Eiffel Tower, the Louvre, and the Pont Des Arts. A statue of Henri IV can be found at the narrowest part of the triangle, which also points to the Pont Neuf, the first bridge built across the Seine.

More Top Articles on LAN

- 10 of the Most Common Mistakes People Make in Planting Design and How to Avoid Them

- Interested But Not Confident? – Know How to be Good at Hand Drawings

- Top 10 YouTube Tutorials for Technical Drawing

La Place Dauphine à Paris (Île de la Cité). Photo credit: Alexander Johmann. Licensed underCC BY-SA 2.0 . Image source

3. Paley Park, Midtown Manhattan, New York City

At just one-tenth of an acre, this park is truly a miniature oasis in a skyscraper jungle. Robert Zion designed the park after William Paley, former chairman of CBS, donated the land as a memorial to his father. The park opened in 1967 and still looks much like it did then. It sits between three buildings, with a 20-foot water wall — which drowns out the surrounding city noise — as the centerpiece. Ivy-covered walls flank the water wall, and the courtyard is home to 17 honey locust trees. Moveable metal tables and chairs are scattered throughout the space. A food kiosk at the entrance invites passersby to come in and sit down for a quick bite and to relax while the city moves past outside.

“Creative Commons Paley Park on a cloudy, chilly late winter afternoon”. By Jim.henderson licensed under CC

4. The Royal Library Garden, Copenhagen, Denmark

Visitors enter this small garden by going through the gates of the National Archives in Copenhagen, which is known as the literary heart of Denmark. Locals simply call this reflective garden, installed in the 1920s, the Library Garden, and it isn’t uncommon to bump into people who work in Parliament on their lunch break here.

The building of the Royal Library, Denmark, on Slotsholmen which dates to 1906, viewed from the northwest. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0. Image source.

5. Art Institute of Chicago, South Garden, Chicago, Illinois

This intimate garden is built on top of a parking garage of the Art Institute of Chicago and opens onto Michigan Avenue. It is a simple design comprised of two raised beds that hold honey locust trees, privet, ground covers, and flowering bulbs. A rectangular pool can be found in the central plaza; the water leads to the Fountain of the Great Lakes, designed by Lorado Taft. Here, planters that double as benches hold cockspur hawthorn trees. Designed by Dan Kiley, the park was installed between 1962 and 1967 and remains one of his best-preserved designs from this time period.

6. Franklin Street Park, Cambridge, Boston, Massachussetts

At a mere 4,400 square feet, this parklet is one of the smallest in the greater Boston area. Located in the Riverside neighborhood of Cambridge, it was rehabbed in 2003 and has been a beloved local spot since then. It is so loved that in 2004, the American Society of Landscape Architects magazine, Landscape Architecture, gave it the “Editors’ Choice” award. The park is easy to find due to its large granite entrance designed by Boston sculptor Murray Dewart. Once inside, it is quiet and serene due to its lush plantings, water feature, and designated areas for children.

Interior of the Franklin Street Park. Photo credit: EECavazos – Own work. Licensed under Public Domain. Image source.

7. John F. Collins Park (formerly Chestnut Park), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Philanthropist Dorothy Haas proposed the building of this park after visiting Paley Park in Manhattan. After she persuaded the William Penn Foundation to fund it, John Francis Collins was hired as the designer. The park opened in June 1979 and is less than one-tenth of an acre. Situated between two buildings, the park’s materials reference the local and native landscapes of the region. Native trees such as redbud, dogwood, sugar maple, hickory, and American holly surround a central fountain made of concrete plinths meant to represent Native American totems. The park was renovated in 2011 and reopened as John F. Collins Park. Visit The Cultural Landscape Foundation for more information about this park. – In cities that are always expanding, green spaces are oftentimes forgotten. But pocket parks show that there really is no excuse to not have public green spaces, and that no matter how small, they can still have a huge impact on the local community. How about your community — are there any notable pocket parks?

Recommended Reading

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

Article by Erin Tharp

Simons Center Bring in the Scientists to Get Gold

Simons Center for Geometry and Physics, by Dirtworks Landscape Architecture, in Stony Brook, New York. Stony Brook University is considered one of the greenest colleges in the United States, so it came as no surprise to designers when the university requested that the design for Simons Center for Geometry and Physics needed to not only meet its high standards for sustainability but to also exceed them. As part of the State University of New York system, the building needed to be at least 20 percent more energy efficient than a baseline comparison and needed to meet the standards to be LEED certified. Dirtworks Landscape Architecture, PC was up to the challenge. Meeting With The Scientists As the firm responsible for the planning, design, and all technical aspects, Dirtworks had a big order to fill. To start the daunting task, the designers met with scientists and faculty to ensure that their design not only met sustainability standards but also fulfilled certain educational goals. One of these was the state of the art technology used in the mechanical system of the building, which, along with the building itself, was designed by architects at Perkins Eastman.

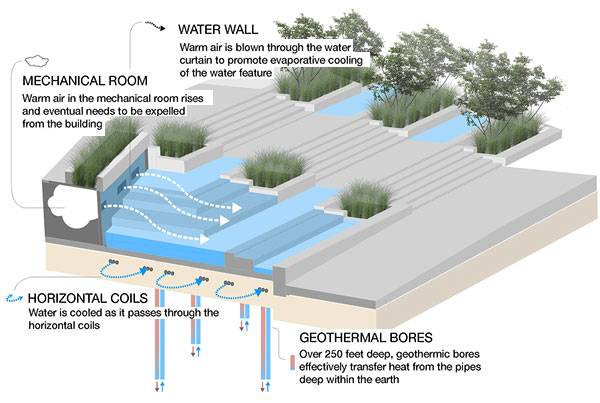

Masterplan of Simons Center. Courtesy of Dirtworks Landscape Architecture

Simons Center for Geometry and Physics

As a way to reduce the energy load of the building, architects placed several mechanical systems for cooling. These systems include air handlers that utilize ice storage and geothermal wells as heat-rejection methods; active chilled beams in the offices to provide low-humidity cooling; and the maximum use of outdoor air and ventilation. David Kamp and his team at Dirtworks created a water feature solely responsible for the cooling of these mechanical systems. The water feature also serves as the introduction to the center and was one of many aspects that helped the site receive LEED Gold Certification.

Diagram of Water feature at Simons Center. Courtesy of Dirtworks Landscape Architecture

Simons Center. Photo credit: Mark Weinberg

- 10 of the Most Common Mistakes People Make in Planting Design and How to Avoid Them

- Interested But Not Confident? – Know How to be Good at Hand Drawings

- Top 10 YouTube Tutorials for Technical Drawing

Simons Center. Photo credit: Mark Weinberg

Looking down on the roof garden at Simons Center. Photo credit: Bruce Buck

Simons Center. Photo credit: Mark Weinberg

The roof garden at Simons Center. Photo credits: Mark Weinberg

Simons Center. Photo credit: Mark Weinberg

- 79% reduction in potable water

- 100% reduction in potable water use for sewage conveyance

- 34% reduction in energy use (based on ASHRAE 90.1-2004)

- 87% of on-site construction waste diverted from landfill

- 21% of total building materials have recycled content

- 27% of total value of building materials are located within 500 miles of the project

All of these combined are what led to the awarding of LEED Gold Certification, certainly a worthy goal that other projects should aspire to. How can this project serve as a model for other universities or public spaces?

Simons Center. Photo credit: Mark Weinberg

Full Project Credits for Simons Center for Geometry and Physics:

Project Name: Simons Center for Geometry and Physics Institution: Stony Brook University/The State University of New York Location: Stony Brook, New York Size: 1 acre; 2 green roofs Date of Completion: 2010 LEED Certification: Gold Award: 2014 Excellence in Landscape Architecture-General Design, Honor Award: Society for College & University Planners Landscape Architect: David Kamp, FASLA, LF, NA Organization: Dirtworks Landscape Architecture, PC Architect: Perkins Eastman Architects, PC Photographer: Mark Weinberg and Bruce Buck Show on Google Maps

Recommended Reading:

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

Article by Erin Tharp

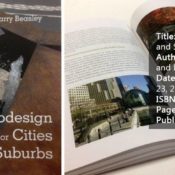

Ecodesign for Cities and Suburbs | Book Review

A book review of Ecodesign for Cities and Suburbs, by Jonathan Barnett and Larry Beasley. In their new book, “Ecodesign for Cities and Suburbs”, co-authors Jonathan Barnett and Larry Beasley use real-world examples to show how ecodesign can be combined with generally accepted business practices and standard development regulations to create successful city planning designs. They prove that our built environment can be designed to adapt to a changing climate and to a rapidly expanding world population while also creating places that are more desirable for living and working

Ecodesign for Cities and Suburbs

Front cover of Ecodesign for Cities and Suburbs by Jonathan Barnett

Inside of Ecodesign for Cities and Suburbs by Jonathan Barnett. Photo credit: Erin Tharp

Inside of Ecodesign for Cities and Suburbs by Jonathan Barnett. Photo credit: Erin Tharp

Inside of Ecodesign for Cities and Suburbs by Jonathan Barnett. Photo credit: Erin Tharp

Inside of Ecodesign for Cities and Suburbs by Jonathan Barnett. Photo credit: Erin Tharp

Pick up your copy of Ecodesign for Cities and Suburbs today!

Review by Erin Tharp Return to Homepage