Author: Stephanie Roa

Element of Chance [Video]

As landscape architects, we often find ourselves trying to tame nature into a designed form. What if, instead of working against natural systems, we invited them into our work, allowing our built work to be shaped by nature? What if, instead of considering our projects to be “complete” the day they are installed, we allow our projects to be more experimental? During the Land8x8 Lightning Talks in Seattle, Dorothy Faris, Principal at Mithun, pondered these type of questions – instead of working against nature, shaping it to a form of our own design, perhaps we should let nature take part in the design process.

With a background in ceramics and art history, Faris was attracted to landscape architecture as an art form – one that sculpts the land and forms our built environment. Similar to an artist, landscape architects know their materials intimately, and test them to create structure and evoke feeling. The material palette of a landscape architect is, however, much different than that of a painter or sculptor. Beyond furnishings and finishes, landscape architects must also consider the forces and flows of nature. This mindset has allowed Faris to approach her work differently – understanding that design is experimental, as there are elements that are completely out of our control.

“Designing with nature is a practice we’ve employed for generations, but allowing design to live and breathe is something the profession might make more room for.” – Dorothy Faris

During her presentation, Faris shared her admiration for ceramic sculptor Robert Sperry. One of ceramic’s great innovators, Sperry had a unique reverence for the materials he worked with, accepting that his control over the end product was limited, and in many ways was out of his hands. As Faris explained it, Sperry was willing to allow “elements of chance” to occur. Comparing her work and the work of her colleagues at Mithun to that of Sperry, Faris asked: “Where is the element of chance in our work? Are we allowing for an outcome we cannot completely predict?”

As she considered how her projects responded to the dictated program or challenges of the site, Faris wrestled with the temperance of her work. While we may like to believe that our projects are to remain true to their original vision, the reality is that our work is constantly evolving. Unlike a painting, our work is not stagnant. Designed spaces are reshaped by the many hands that touch it, and the communities that make it their own. Similar to Sperry’s pottery in the kiln, we may be better off letting go, embracing landscape design as an evolving system.

So, let’s consider allowing the spaces that we create to be molded into an entirely different new landscape. Like Faris, we may find a certain beauty to the evolution.

—

This video was filmed on June 7, 2018 in Seattle, WA as part of the Land8x8 Lightning Talks sponsored by Anova Furnishings.

Landscape Stories as Catalysts of the Shared City [Video]

The ways in which citizens engage the landscape reveal a community’s values and priorities. During the Land8x8 Lightning Talks in Seattle, Nate Cormier, Principal at Rios Clementi Hale Studios, conjectured that American urbanism has a storytelling problem.

Arcadian and Utopian mythologies of the West were used to sell sprawling patterns of land use and transportation which encouraged people to live in low-density environments and to take their leisure in private. Through media like Sunset Magazine, the California backyard grew into an American ideal. The resulting landscape of inequity has in recent decades been compounded by virulent NIMBYism (“Not In My Backyard”) which resists infill housing and makes living in job-rich cities increasingly unaffordable for young people.

While he hopes that society continues to wrestle with these injustices, Cormier sees a unique role for landscape architects in telling the optimistic story of the “shared city.” As cities become denser, more and more of their residents will need to pursue leisure in common rather than in private backyards. How can the public realm respond in a way that makes room and makes meaning for all citizens?

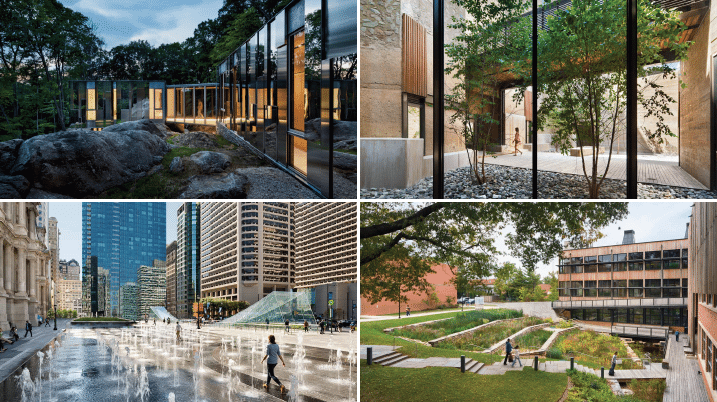

Photo: Grand Park | Rios Clementi Hale Studios

Cormier shared three examples from the work of Rios Clementi Hale Studios—Grand Park in Downtown Los Angeles, Downtown Park in Palm Springs, and Jones Plaza in Houston’s Theater District. These projects demonstrate how public space can leverage cultural diversity and site specificity to delight visitors and inspire urban living. These kinds of comfortable civic places are essential catalysts of the shared city spirit we need to accommodate growing urban populations with grace.

Based in Los Angeles, Rios Clementi Hale Studios is a multi-disciplinary design house with an adventurous portfolio ranging from large parks, performance spaces and gardens to tableware, surfboards and a new clothing line. Their practice celebrates the connection between people and place. They believe that good design connects people, celebrates their stories as individuals, and brings people together, allowing for new stories to be created.

“Design is never without story. It connects people to each other and the world around us. Together we work beyond boundaries to reveal, explore, and invent designs that amplify experiences.” – Rios Clementi Hale Studios mission statement

—

This video was filmed on June 7, 2018 in Seattle, WA as part of the Land8x8 Lighting Talks sponsored by Anova Furnishings.

Into the Weeds [Video]

Imagine the world is at the edge of an apocalypse – that Earth’s life has been greatly damaged and resembles a disastrous wasteland. The grim images painted in science fiction films are generally understood to be out of the realm of real possibility. However, during the Land8x8 Lightning Talks in Seattle, Michelle Arab, Director of Landscape Architecture at Olson Kundig, asks us to consider this landscape for a moment. Arab begins her presentation by evoking the imagery of the barren landscapes of Blade Runner 2049 – a stark vision of a world shattered by some nameless disaster – and asks us to consider the role of landscape architecture in a post-apocalyptic world. What lessons might we take from this type of world and how we will design in it?

At a time where natural disasters such as hurricanes, wildfires, and droughts are increasing in frequency and intensity worldwide, are we closer to an apocalypse than we anticipated? It doesn’t take much digging to find images of real world landscapes wrecked by natural disaster – not too dissimilar from those portrayed in sci-fi films. As resources become more precious and intense weather events more common, what does the future of our cities look like? With climate change accelerating and impacting communities worldwide, it may be time to open our eyes and prepare for the world that is to come.

As we begin to see a increased incidence, duration, and magnitude of events like sea level rise and flooding, rising urban temperatures or urban heat islands, urban sprawl, and reduced availability of water, the implications are clear: human and natural systems must become more resilient to expected changes. By coming to terms with this reality, we have the opportunity to be better prepared and to rebuild our cities with climate change in mind. Instead of grappling with the aftermath, we can take action today to not only mitigate our impact on the global climate, but also adapt to the changes that are coming – and those that are already here.

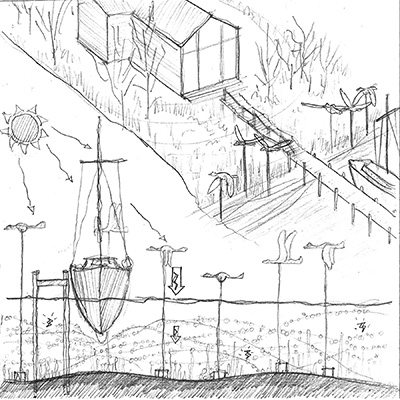

Image: Michelle Arab

Just as in the movies, the rebuilding process provides an opportunity to chart a new path. Rethinking the design, construction, and operation of our cities in order to mitigate climate change and increase resilience toward its effects is an important and exciting undertaking. A shift is taking place towards building cities that work with the unpredictable events that are to come. Resilient cities reduce their vulnerability to extreme events by responding creatively in advance of economic, social, and environmental challenges. By rethinking our water efficiency, building materials, plant selection, and transportation systems, our cities can have an increased capacity to cope with climate change events.

Hopefully, our Earth will never reach such a state of disrepair as is portrayed in movies. Instead, designers and policymakers will take action and we will see cities transform, adapting to not only survive in the face of the “apocalypse”, but thrive.

—

This video was filmed on June 7, 2018 in Seattle, WA as part of the Land8x8 Lightning Talks sponsored by Anova Furnishings.

10 Billion Mouths [Video]

The United Nations projects that the world’s population will be 9.8 billion by 2050, with roughly two-thirds of those people living in urban areas. To feed these nearly 10 billion mouths, it is estimated that farmers will have to produce 70% more food by 2050. However, large-scale farming is rapidly diminishing, and most available farmland has suffered from years of poor practices that led to soil erosion. This, coupled with issues of drought and rising transportation costs, has led some to believe that the future of farming might just be in the city – and indoors.

During the Land8x8 Lightning Talks, Michael Grove, Principal at Sasaki, an international planning and design firm, asserted that “…productive landscapes must play a critical role in our cities.” Michael revealed how his firm is experimenting with new forms of farming in cities across the world. With agriculture and urban development being the two largest systems impacting the landscape, it is clear, Michael states, that landscape architects should take notice.

Vertical farming, a practice that Michael highlights, involves stacking plants on shelves, instead of laying them out horizontally across large plots of land. The goal of this practice isn’t just to save space. It’s to bring fresh food to remote places previously unsuitable for growing plants, find an economical way of producing food, and reduce the environmental impact of getting that food to the consumer. Vertical farming prevents groundwater pollution, reduces CO2 emissions from delivery trucks, and lessens soil erosion. It also requires only a fraction of the acreage and water —anywhere from 90 to 97 percent less—than traditional farms do. With vertical farming, Michael says, “Architects have begun to ask the question of how cities can contribute to food production.”

“Vertical farms are an opportunity to leapfrog to the next generation of how cities source their food.” – Michael Grove

Although still experimental, many entrepreneurs and innovators around the world have successfully converted this concept into reality. For example, Freight Farms, headquartered in Boston, transforms old shipping containers into productive farms and is already a mainstay on many college campuses around the country. And San Francisco vertical farming startup Plenty, just received $26 million in funding from investors such as Bezos Expeditions and Innovation Endeavors.

Sunqiao Urban Agricultural District, Sasaki

Expanding on his own work, Michael shared how the Sunqiao urban farm project in Shanghai, China will implement innovative ideas to provide food for the growing population. The Sunqiao urban farm will supply much of the city’s leafy greens locally, year-round, and at an economically viable scale – all through vertical farming. This system will not only increase production yields by 40 to 100-times, it will also act as a living laboratory for residents to learn about how their food is grown.

Michael urges landscape architects to integrate productive landscapes into urban centers – creating designs that will change how cities source their food. In doing so, we may be able to feed a growing population that is also hungry for fresh, locally sourced, environmentally conscious food.

—

This video was filmed on September 28th, 2017 at ASLA’s Center for Landscape Architecture in Washington, DC as part of the Land8x8 Lightning Talks sponsored by Anova Furnishings.

Deep Collaboration: Ecology, Research, Design [Video]

In the face of climate change, urbanization, and social unrest, landscape architects are being asked to do more. No longer can a landscape architecture project simply be beautiful; it must also remedy environmental degradation, address social inequity, support economic development, strengthen communities, and so much more. As the complexity of challenges grow, the importance for a collaborative design process – one that invites new disciplines and diverse perspectives – becomes evident. As an urban ecologist and architect, Stephanie Carlisle advocates for this new way of working – believing that a deeper connection between urban ecologists and designers will result in the creation of better cities and a transformational impact. During the Land8x8 Lightning Talks, Stephanie revealed the synergies between ecologists and landscape architects and emphasized the urgency for greater communication between architecture and the sciences.

“The way forward is a radical embrace of transdisciplinary collaboration and expansion of our definition of design and who is allowed to participate in the design process.” –Stephanie Carlisle

Both urban ecologists and landscape architects are focused on the intersection of the natural and built environment. However, despite their synergies, science and design are not always connected. Urban ecology is a profession rooted in science, which studies the relation of living organisms with each other and their surroundings in the urban environment. Urban ecologists see the entire city as an ecosystem – one that is influenced by the interactions between humans and nature. Urban ecology provides a framework for describing the structure, function, and composition of urban landscapes. Landscape ecology should inform the design approach, to address the changing context of the built environment. Stephanie asserts that for urban ecology to be a useful field and framework for design practice, landscape architects must become more familiar with the methods by which urban ecologists ask questions and interpret data and must begin to make room for targeted ecological experimentation in their projects.

Trained in Architectural Design and Urban Ecology, Stephanie holds a Master of Architecture from the Yale School of Architecture and a Master of Environmental Management from the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. As Principal at Philadelphia-based architecture firm KieranTimberlake, Stephanie works as an intermediary between the KieranTimberlake Research Group and project architects to facilitate a greater integration of research within all phases of the design process. Her work investigates the interaction between the natural and constructed environment, including environmental and building systems, urban ecology, landscape performance, and life cycle assessment (LCA).

Stephanie’s work has allowed her to explore the processes that underlie performance and test her design interventions. “We are constantly looking for a way to integrate research into design practice, finding, or rather creating, space for designed experiments,” says Stephanie. For example, she has been experimenting and testing several green roofs on KieranTimberlake buildings. As a living system that experiences growth and change, a green roof is an interesting research space for understanding the dynamics of urban systems. This multi-year project examined plant community dynamics on a series of mature intensive green roofs, built over the last ten to fifteen years. By studying how plant communities adapted and evolved over time, Stephanie believes we can change the way we design our work to have a bigger impact.

“I see the strength of landscape in integrating environmental performance with designed technological systems and adapting urban designs to social and ecological challenges.” –Stephanie Carlisle

In order to facilitate communication between the two professions, Stephanie is Co-Editor-in-Chief at Scenario Journal, an online publication devoted to showcasing and facilitating the emerging interdisciplinary conversations between landscape architecture, urban design, engineering, and ecology. She is also a lecturer in urban ecology at PennDesign, arming emerging professionals with tools to be better collaborators. The PennDesign coursework prepares landscape architecture students to employ fundamental ecological mechanisms to effectively model landscape performance over time.

Environmental, urban, and social issues are all interrelated, and in order to be truly transformative, we must work collaboratively. Stephanie believes that by collaborating with urban ecologist, designers can gain a better understanding of the urban environment and the impact of their work, and ultimately create natural environments that are good for both people and nature.

—

This video was filmed on September 28th, 2017 at ASLA’s Center for Landscape Architecture in Washington, DC as part of the Land8x8 Lightning Talks sponsored by Anova Furnishings.

3rd Annual ANOVA Grant for Emerging Professionals

Anova Furnishings’ Grant Competition is back again this year, offering emerging professionals the opportunity to attend the 2018 ASLA Annual Meeting and EXPO in Philadelphia. Centered around a different topic each year, the competition invites participants to submit a short essay and a quick napkin sketch between April 13 to May 14, 2018 for the chance to win a $2,000 grant toward conference expenses. A panel of three practicing Landscape Architects will select the 21 best responses to be awarded the grant.

Participants of the 2017 Anova Grant were asked to address the issues of climate change within their region. 1st place winner, Steve Makrinos of Annapolis, MD, sketched Electric Reefs on Chesapeake Bay waterfronts, which would act as resilient buffers–rapidly reestablishing oyster reefs and subaquatic vegetation.

To get the inside-scoop on what the jurors are looking for, I interviewed two of this year’s jurors, Stephanie Rolley, Professor and Department Head of LARCP at Kansas State University, and Annette Wilkus, Partner at SiteWorks. Here’s what they had to say. Interviews have been edited and condensed.

First, tell me a bit about the competition, and why you wanted to be a part of it.

SR: I was very excited when Eric Gilbert, the CEO of Anova, called and asked if I would be interested in participating as a juror because I have been so impressed by Anova’s support of emerging professionals. I have been involved with ASLA for many decades with a focus on students and young professionals, and it’s so hard to get students to attend the ASLA Annual Meeting because of the cost to attend. We need to have them there for us to be able to benefit from their shared knowledge.

AW: I thought it was really amazing that a furniture company wanted to promote education for young professionals and make sure that they can get to the ASLA Annual Meeting. I thought it was a very interesting idea that Eric had and I’ve never seen any other similar company do something like this. I think it’s really important to try to encourage young professionals to be involved in the profession and our national organization, and this competition really encourages that.

What will the jury be looking for in a winning submission?

SR: One of the themes of this competition that stays true over the years is that the primary focus is on ideas and people expressing those ideas through drawing – focusing more on conveying the concept and worrying less about the presentation. It’s a unique aspect of what we do for this competition because so much of what we do in design is focused on very final highly developed graphics. This competition is focused on having people present their ideas and do it in a way that is uniquely personal to them and maybe not professionally typical.

AW: To me, it’s seeing how thoughtful the submitter is – and if they can write complete sentences is always a good thing. I was one of the first jurors and I’ve always pushed that the napkin sketch isn’t about making something pretty. It’s about being in a meeting and being able to communicate something quickly. This is a great way to practice quickly getting your thoughts across – drawing can help you explain something that will click into the audience’s mind quicker than just talking would. That’s why the sketch is really important, but it does not have to be perfect. It just needs to match what you’re talking about.

What about those of us who are still working on our drawing abilities? Are we still encouraged to apply?

SR: Definitely. And, when you look at the gallery of previous winners, you can see that. You can see that some people have a very refined hand and can probably make anything look like a work of art and there are others who are less refined and equality enthusiastic about their ideas.

AW: Oh yeah. Absolutely!

Can you describe examples of past winning submissions and what makes a strong submission?

SR: The strong submissions have a very strong imagination and focus on innovation and thinking about the future – moving beyond current conversations and ideas about landscape architecture to envision what will be important for the future. And the other trend is an enthusiastic drawing – not highly refined, just very enthusiastic that shows someone’s passion for their idea.

AW: There’s one I can remember that was probably a more refined sketch than I would have expected, but it was talking about a really innovative way to help suggest a solution for some of the environmental things that were happening in their community. It was a really innovative way of taking a boat and adding sun panels. It had a short written part that matched the sketch perfectly.

This competition is exclusively for up-and-coming landscape architects, and the winners are awarded $2,000 to attend the 2018 ASLA Annual Meeting in Philadelphia. Why do you think it’s important that young professionals attend the Annual Meeting?

SR: I think it’s essential because young professionals are the future of our profession. They need to be leading our profession, and one of the best ways to do that is to come to the biggest collection of landscape architecture professionals in the U.S. and participate in the conversation. I think for years the meetings have been accessible largely to people who are pretty far along in their careers because it is an expensive venture to travel to the host city and attend the Meeting, so it makes a big difference that Anova is making this accessible to younger people. When you look at the number of awards given, that’s critical because it’s not just one or two special people being invited to attend the Meeting. Through this competition, Anova is helping to change the demographic of ASLA.

AW: Because you can learn so much. It gives you exposure beyond what office you’re working in. You can see what other practitioners are doing. Sitting in the lectures you can learn quite a bit ranging from super innovative to going back to the basics of communicating better, or providing better construction drawings. There are some really technical presentations at the Annual Meeting and then there are some really innovative things happening. You get to see the big names in landscape architecture and hear them speak. It gets you involved in the profession. We have a hard enough time explaining what landscape architects do, so it’s great to be in such a motivational space with others in your profession.

This year’s competition asks participates to describe a space that influenced their career in landscape architecture, which can help others relate to the profession. If you could enter the competition, how would you respond?

SR: Upper Bear Creek in Colorado was an important part of my childhood. Playing in the water, sliding down rock chutes, trying to catch fish, weaving necklaces of flowers from the bank, and falling asleep to the sound of the rapids were experiences that shaped my appreciation for nature. When I realized that landscape architects design places that immerse others in those experiences and many more, I knew I’d found my future.

AW: That’s a tough one for me because it wasn’t really a place or space that influenced me. I was working at a greenhouse and the landscape architect there introduced me to landscape architecture. The profession wasn’t really acknowledged in the 70’s, so I wouldn’t have heard of it if not for him.

—

Through this grant, Anova is not only increasing the diversity of voices at the Annual Meeting, but also providing an opportunity to showcase the profession and its ability to help solve today’s challenges. To learn more about the competition and submit your entry, visit the competition website. Submissions will be accepted from April 13 to May 14, 2018.

Workaround [Video]

In the spring of 2015, tension and unrest erupted in Baltimore, bringing the issues of racism and inequality to the center of national media attention. Since then, these disparities have only become more prevalent as the voices of unrest grow louder – including in Ferguson, MO, Charleston, SC, and Charlottesville, VA to name only a few. These events have been a call to action for many, leaving many to consider how they can bring about change in our social system. While such issues may at first seem to be beyond the reach of design professionals, Richard Jones, President of Baltimore-based design firm Mahan Rykiel Associates (MRA), believes that it is necessary for the profession to address inequality so that we may better meet the needs of those we serve. During his presentation at Land8x8 Lightning Talks, Richard shared how his firm is exploring the intersection of landscape architecture and racial inequality and a design firm’s role in addressing social injustice.

In the field of landscape architecture, it is critical to hear from a diversity of voices throughout the design process to ensure a successful project – one that meets the needs of all community members. However, the demographics of our nation is not reflected in the profession, where African Americans and Latin Americans together account for 17 percent of graduating landscape architecture students. In a field intended to create spaces that bring people together, new perspective is needed to ensure that landscape architecture reflects the communities it serves. As Richard states, “The future of our profession in a world that looks like this one is hinged on developing diversity in our practice which more accurately represents the diversity in our country.” MRA is working to address the lack of diversity in the profession and provide just and equitable spaces to underserved communities by focusing on inequality in schools.

To tackle the issues of social and environmental inequality, Mahan Rykiel created their Social Impact Studio. As Richard explains, “The studio focuses primarily on collaborative action to give voice to the underserved so that they might be partners and leaders in rebuilding their neighborhoods and celebrating the richness of their culture and history.” The first project launched out of this studio, Project Birdland (2017), explored how they could address social injustice in their community, while operating within the bounds of the profession. While working on the Anthem House, a mixed-use development located within the Locust Point neighborhood of Baltimore, Richard found the work-around he had been looking for through the Chesapeake Bay Critical Area “fee-in-lieu” mitigation payments. Because the team couldn’t replace all of the trees that were removed during the development, they were facing to mitigate for trees and vegetation lost during the development process. By partnering with the City of Baltimore and Anthem House ownership, Mahan Rykiel was able to re-direct these fees as seed money for a project that benefits both the local community and environment.

The project started with the idea of taking the trees to a nearby underserved school, Francis Scott Key Elementary/Middle School (FSK), but after meeting with the school principal, the scope expanded to the creation of a classroom curriculum, the design and fabrication of birdhouses, and the creation of an outdoor bird habitat and learning lab – interweaving the project with design-based environmental education. The project addresses the shortfalls in STEM-based learning in the city school system and provides an opportunity for students at the school to gain knowledge in ecology and foster an appreciation for the natural environment.

The habitat design at FSK re-envisioned the school’s entrance to be an outdoor educational and learning space, integrating an array of landscape elements that tie into STEM curriculum objectives. The outdoor bird habitat was planted with over 3,600 native plants and provides students with an opportunity to learn about nature (in a city where students may not be exposed) and be excited to go to school. In conjunction with the habitat design, the school adjusted their curriculum to include lessons on habitat and ecology. Learning directly from urban ecologists and designers, the students were challenged to study the impacts of urbanization and habitat fragmentation on urban song birds. In addition, sixth- and eighth-graders took part in a competition to design birdhouses out of Popsicle sticks, with two winning prototypes used as inspiration for the creation of wood and steel birdhouses designed by Gutierrez Studios and placed within the habitat.

What would have been a typical tree mitigation requirement, became an opportunity for Richard’s team to address inequity in their own city and introduce concepts of design and natural environments to an underserved population. Not only did the project improve the quality of the school’s campus, it more importantly took a step towards addressing issues of inequality in the environment, education systems, and the profession. A catalyst for new partnerships between developers, educators, environmental designers, and neighborhood communities, Project Birdland shows us how landscape architects can facilitate the change they wish to see within our own field and in society at large.

So, the culmination of the effort is a project that builds community, extends curricula, educates students, and most importantly, instills within the children at FSK the belief that they can dream beyond the limits of their current circumstance – to see within themselves the potential to be a scientist, a designer, or a landscape architect, and, maybe most importantly, to see tangible proof that they can positively affect the environment around them. – Richard Jones

—

This video was filmed on September 28, 2017 at ASLA’s Center for Landscape Architecture in Washington, DC as part of the Land8x8 Lightning Talks sponsored by Anova Furnishings.

Beyond Our Landscapes: Interdisciplinary Research and Design for Health [Video]

At a time when environmental crises are becoming more prevalent and the health industries are acknowledging the critical role the environment plays on human health, designers are stepping up to explore how landscape architectural interventions can address health issues. The profession of landscape architecture is poised to tackle the issues of both human and environmental health, states Jorge “Coco” Alarcon of Peru at Land8x8 Lightning Talks. Promoting health in the fields of architecture and landscape architecture, Coco shared how he has leveraged his design background to improve the health of impoverished communities.

Holding a Master’s of Landscape Architecture degree and working for the University of Washington, Coco’s research focuses on the relationships between green spaces and vector-borne diseases. As co-founder of the Informal Urban Communities Initiative (IUCI) – a design activism, research, and education program based in Peru – Coco has had the opportunity to design and implement several projects in neglected communities within Peru. During his presentation, Coco touched on four projects that he has been working on in Peru, all of which highlight the importance of a community-participatory approach, and bridges the divide between research and intervention, and landscape architecture and health. Coco also monitors and evaluates all of his projects to understand how landscape architectural interventions can impact human and ecological health – including addressing water quality, vector-borne disease, nutrition, and mental health and well-being.

Fog Water Farm Park includes a public park with a playcourt, space for community gatherings and a series terraces planted with drought tolerant and productive vegetation. A large-scale fog collection system harvests water, while large capacity tanks store water for irrigation during the dry season. (Photo: IUCI)

The first project he shared, titled, “Gardens, Green Spaces, Health and Wellbeing,” took place in Lomas de Zapallal, a poor community near Lima, Peru suffering from the afflictions of food and water insecurity, the lack of green and recreational spaces, and poor mental health and well-being. By partnering with the community and hosting several community meetings, Coco and his interdisciplinary colleagues determined three solutions to address these issues: building household gardens, creating a community park, and providing a sustainable water source. IUCI helped the community build fifty domestic gardens to provide extra food and relaxation space around individual’s homes, create a sustainable water supply by construction six fog harvesting systems, and build a community park that provides public farming land, stores enough water to irrigate the land, and allows for active recreation. These interventions have shown to improve access to food and water, improve quality of life, and decrease stress for the community.

The second project, “Residential Gardens as a Health Strategy in Impoverished Communities in Developing Countries,” focused on improving housing conditions in order to mitigate health problems. Iquitos, a Peruvian city in the Amazon rainforest, suffers from health problems that include tuberculosis, malnutrition, and infectious diseases related to poverty and mosquitos. Working with health professionals, Coco’s team recommended renovating the backyards of homes to mitigate these health problems. These renovations allowed the backyards to provide an additional food source, manage water more efficiently, and improve maintenance, reducing mosquito exposure. The third project, “Exploring Relationships Between Vector-Borne Diseases and Landscape Architecture,” is a research-based project. Aedes mosquitoes – indigenous to tropical and subtropical and climates – spread life-threatening diseases including dengue, Zika, and yellow fever. Using landscape architectural theory and approaches to study these vector-borne diseases, Coco’s team defined the role that landscape architects have on Aedes mosquitoes and how to make the landscape more resilient to vector-borne diseases. Through extensive research, interviews, and field visits, Coco and his team created a checklist for designers to utilize in the field to both identify if a site is at risk and instruct designers on how to control mosquitoes.

This Terrace Infiltration Garden replaced six tons of trash with plants for food, medicine, habitat, and beautification. (Photo: IUCI)

The final project he shared, “Impact of Landscape Architecture Technologies on Human and Ecological Health,” is also based in Iquitos. Claverito, one of several informal flooding communities, is largely a neglected space where land pollution, the lack of clean water and sanitation, and poverty have created many health problems. By talking with the community and explaining how the expertise of landscape architects could align with some of the community’s needs, they were able to work together to develop design solutions. Coco and his team assisted in the removal of six tons of trash from the community and redesigned the main entryway to create a welcoming and safe environment for residents to be proud of. Once a heaping mound of trash with an informal staircase entering the community, Coco’s team built stairs and gardens that infiltrate and clean runoff from the city above, replacing trash with thousands of medicinal and edible plants. They also worked with the community to design and construct thirty floating gardens, providing residents with a place to grow their own plants and beautify their surroundings.

“Landscape architects are now leading activism, research, and science across fields, opening a new scope of practice that is going to be critical in the future — landscape architects as global health leaders.” – Coco Alarcon

Coco’s work extends beyond landscape architectural interventions; they include improving mental and physical health, nutrition, biodiversity, and reducing vector-borne diseases. As he works to gather evidence for green space design, develop prototypes to be easily implemented, and define a set of tools and protocols for the evaluation of impacts that green spaces have on health, Coco encourages landscape architects to push beyond the typical boundaries of the design profession. Coco stresses that the role of landscape architecture extends beyond design and is working to build the capacity of designers to work efficiently with poor urban communities.

—

This video was filmed on September 28th, 2017 at ASLA’s Center for Landscape Architecture in Washington, DC as part of the Land8x8 Lightning Talks sponsored by Anova Furnishings.

Forest and Architecture [Video]

There is something so serene about being in a forest. Whether it’s the peaceful silence or beautiful surroundings, being immersed in nature has actually been proven to affect you both physically and emotionally. However, while the forest is an environment often preferred by humans, it displays little resemblance to the loud and crowded cities in which most of us choose to live. With an increase in global urbanization, there is a need to adapt the urban environment, bringing aspects of the forest into our cities. During her presentation at Land8x8 Lightning Talks, Jana VanderGoot, architect and founding partner at VanderGoot Ezban Studio, explores how we can create cities that mimic the benefits of the forest.

Forests have the ability to capture carbon, moderate temperature, purify water, and provide food and habitat for an abundance of wildlife – all of which are necessary for human existence. This is why VanderGoot believes that urbanists should look to the forest while designing a city where humans can not only live, but also thrive. More recently, we’ve seen nature play a larger role in architecture. From treating rainwater to heat reduction and habitat creation, buildings are beginning to act as living organisms. VanderGoot is intrigued by the ways in which buildings act as extensions of larger urban ecological networks, sustaining and enhancing the qualities of the natural landscape.

Architecture and the Forest Aesthetic

VanderGoot is interested in the intersection of architecture and landscape. Holding both a Master of Architecture from the University of Virginia and a Master of Landscape Architecture from Harvard University, she imparts a landscape-based approach to urbanism. As an Assistant Professor of Architecture at the University of Maryland, VanderGoot encourages her students to design in harmony with nature. Her recently published book, Architecture and the Forest Aesthetic: A New Look at Design and Resilient Urbanism, is a collection of twenty-one case studies exemplifying the integration of urbanism and the forest. Using forest as model, metaphor, and method, this book re-imagines architecture and urbanism by allowing the forest to be a prominent aspect of design.

As VanderGoot describes, the forest is much more than just a collection of trees or plantings, but the interrelationship between those parts.

In her presentation, VanderGoot shared one of the case studies represented in the book, Table in Rome 2: Forum as Planted Field. This case study utilized an abstraction of the forest to explore a different feature of the forest – collectivity. As VanderGoot describes, the forest is much more than just a collection of trees or plantings, but the interrelationship between those parts. The case study was a semester-long project, utilizing an interactive art installation – funded by a University of Maryland Creative And Performing Arts Award – consisting of a vertical plank with movable wooden dowels, resembling the forest wall. This surface was manipulated throughout the semester, as students and visitors were invited to move the pieces as they desired. Exemplifying the progression of a forest, the exhibit changed over time, as groups rearranged with the dowels, shifting the symbolic forest.

Similar to trees within a forest, buildings are only one part of a larger field that make up the urban environment. VanderGoot reminds us that whatever we create, people will make it their own, and it will in-turn change over time. As this case study shows, the urban landscape, just like the forest, is constantly in a state of flux –adapt to and allow for change in order to survive. By considering architecture as a part of a collective space, rather than an individual element, buildings may begin to participate in the landscape. As VanderGoot puts it, “At the foundation of architecture is a shifting landscape.”

—

This video was filmed on September 28th, 2017 at ASLA’s Center for Landscape Architecture in Washington, DC as part of the Land8x8 Lightning Talks sponsored by Anova Furnishings.

The Next Green Revolution [Video]

Despite their ability to treat stormwater, cleanse air, and improve mental health, plants are too often an afterthought in urban design projects. What is often considered decoration or “parsley around the roast,” as famed landscape architect Thomas Church describes it, may actually have the potential to address the challenges of urbanization. That’s what Thomas Rainer asserted at Land8x8 Lightning Talks, announcing “I think it’s time to re-evaluate how the profession of landscape architecture approaches planting design.”

A leading voice in ecological landscape design, Rainer is among the cohort of practitioners who are turning away from conventional horticultural practices, which encourage arranging plants as individual art pieces, and drawing inspiration from the way plants grow in nature. He states that “when you go into the wild and see all the different types of conditions and the vast plant communities that are probably even better at adapting – more biodiverse and more pollinator friendly, and they hold stormwater even better – you realize we’re missing the mark by not innovating with planting design.” By researching the way plants grow in nature, Rainer has found inspiration for the design of urban landscapes.

Naturalistic plantings designed by Claudia West fill this bioretention facility in Lancaster, PA for seasonal intrigue. (Photo: Phyto Studio)

Thomas Rainer and his colleague, Claudia West, made a name for themselves in the naturalistic landscape movement with a book they co-authored in 2015, “Planting in a Post-Wild World: Designing Plant Communities for Resilient Landscapes”. In 2017, they, along with Melissa Rainer, started Phyto Studio, a niche landscape architecture firm dedication to the design of plant communities. In nature, plants are grown in communities, Rainer explains, which intermingle and thrive off of each other. By mimicking this type of communal relationship we see the in wild, we are able to create landscapes that are captivating year-round, while remaining easy to maintain. While this design approach isn’t new – Dutch garden designer, Piet Oudolf, is an early pioneer of the naturalistic movement – these ideas have only recently been brought to the urban environment. For example, the High Line in New York City, and the Laurie Garden in Chicago implements this type of planting aesthetic.

“When you go into the wild and see all the different types of conditions and the vast plant communities that are probably even better at adapting – more biodiverse and more pollinator friendly, and they hold stormwater even better – you realize we’re missing the mark by not innovating with planting design.” – Thomas Rainer

Rainer sees plants as dynamic, engineered systems and has been exploring the qualities of plants to create landscapes that are functional, beautiful, and diverse. To better understand how we can take these wild plant communities and design plantings that thrive in cities, Rainer shares his approach to planting design, starting with choosing the right plants. By using plants that work in harsh urban conditions and are suitable to grow in these environments without relying on soil enhancements and irrigation, the plants will be easy to maintain and guaranteed to thrive. Next, Rainer explains, instead of creating separate, distinct clumps of different plants, use a layering approach that densely assembles groupings of plant species. By selecting plants that are compatible with each other, Rainer is able to achieve a planting design that is beautiful, diverse, and low maintenance.

For those who are concerned that this type of planting will look formless or weedy, Rainer notes that there is a right balance to strike in naturalistic planting design. The design should interpret nature, but not look too “wild.” By using strong architectural frames, and selecting the right, showy plant material, the design intention will be legible. “And I think once people embrace these as tools, we’ll have a new expressive age in terms of planting design,” Rainer asserts.

—

This video was filmed on September 28th, 2017 at ASLA’s Center for Landscape Architecture in Washington, DC as part of the Land8x8 Lighting Talks sponsored by Anova Furnishings.

Transforming Tysons [Video]

“Why just make something, when you can create something that matters?” That’s the firm slogan that Stephanie Pankiewicz, Partner at LandDesign, considers throughout every project, and especially as she has had the opportunity to completely transform Tysons, VA. Currently known for its office parks, shopping malls, and traffic congestion, the future vision for Tysons is that of a high-density city — with walkable streets, an iconic skyline, and quality public spaces. With 14 active projects in Tysons, LandDesign is uniquely positioned to lead the city’s transformation, create something that MATTERS to the community, and set precedent for edge cities around the globe. However, communicating these large-scale changes to the many stakeholders, community members, and county officials has had its challenges. During the Land8x8 Lightning Talks, Stephanie shared how her company has utilized new and innovative technologies to best convey their vision for a vibrantly transformed Tysons.

Image: LandDesign

Tagged by Washingtonian as “what may be the most ambitious suburban redevelopment project not just in Washington, but in all of American history,” the Tysons redevelopment project is a game-changer for the region. Currently a sprawling suburban office park with 167,000 parking spaces, or, as Washingtonian puts it, a “4.3-square-mile tangle of parking lots and office parks that’s long been considered one of the least habitable parts of Washington,” Tysons caters to cars not people. In 2014, four new metro stations opened on Metrorail’s Silver Line, increasing the area’s ease of access and bringing a direct connection from downtown DC to Tysons. Taking advantage of the new transit, county officials initiated a 40-year urbanization plan defined by a walkable urban center, seamlessly integrated public transportation, and acres of parkland. Envisioned at Fairfax County’s new downtown, it is estimated that by 2050 Tysons will be home to up to 100,000 residents and 200,000 jobs in that year.

With 1,600 acres of land undergoing construction, such a transformation is hard to fathom – especially for the roughly 19,600 existing residents who may not be so sure about all of this development in their backyard. To convey their vision, LandDesign utilizes 3D visualization, including virtual reality headsets and 3D animations. A grassroots effort among employees, LandDesign uses these tools as a storytelling technique. As Stephanie explains, “To go from surface parking lots to a new downtown with 19 story buildings is quite a transformation, and the neighbors around it are in single family homes, primarily…to imagine going from your single family neighborhood, a few minutes’ drive away, to a new downtown that is going to have 19 and 20 and 22 story towers is…quite a change. And to be able to explain that in 3D has been very critical.”

The use of 3D technologies have become more prevalent in the design industry, not only as a tool to collaborate with team members, but also to engage the community and realistically express a design idea to those who may not be able to visualize through the typical 2D plan renderings.

The use of 3D technologies have become more prevalent in the design industry, not only as a tool to collaborate with team members, but also to engage the community and realistically express a design idea to those who may not be able to visualize through the typical 2D plan renderings. 3D animations allow users to get a better sense of scale, and a real understanding for how the built product will look and feel. Stephanie adds, “It is also very authentic, which again is very important to the community members, because they don’t want to come to a meeting and think they are seeing a Photoshop montage, they want to know when this park is coming.”

Stephanie urges designers to go beyond the typical use of these 3D tools, as representational imagery, and to instead utilize 3D technology to better understand topography, materiality, scale, and the ultimate functionality of a space. With the assistance of such technology, Stephanie’s team was able to assure neighboring residents, work more collaboratively with team members, and receive county approval – moving one step closer to a new Tysons.

—

This video was filmed on September 28th, 2017 at ASLA’s Center for Landscape Architecture in Washington, DC as part of the Land8x8 Lighting Talks sponsored by Anova Furnishings.

Rising from the Rubble: 1500 Design Challenges for the Emerging Future [Video]

On August 11, 2017 in Charlottesville, VA, amidst signs of hatred and spewed words of bigotry, violence erupted as white nationalists clashed with counterprotesters, leading to one person killed and 19 injured. The aftermath of the Charlottesville riot, spurred by the city’s plans to remove symbols of its Confederate past, reignited the debate over what should happen with Confederate landmarks in cities across the country.

On the Land8x8 Lightning Talks stage, Harriett Jameson Brooks, landscape designer at MVLA, shared her deep connection with Charlottesville, and how she turned to her profession as she grappled with this blatant display of hate and racial tension that did not match how she saw the progressive, democratic city.

Since the upheaval in Charlottesville, a movement to remove Confederate memorials from public property has gathered steam. While many argue for the preservation of such memorials as a reminder of the country’s history, others regard them as glorification of a shameful time in American history. Harriett understands the desire to preserve history – if only to impart important lessons about the ugliness of the past – however, she confesses that the desire to hold on to tradition is “also a way of justifying our inertia and our hesitancy of picking the past over the future, choosing fear over courage and possibility.”

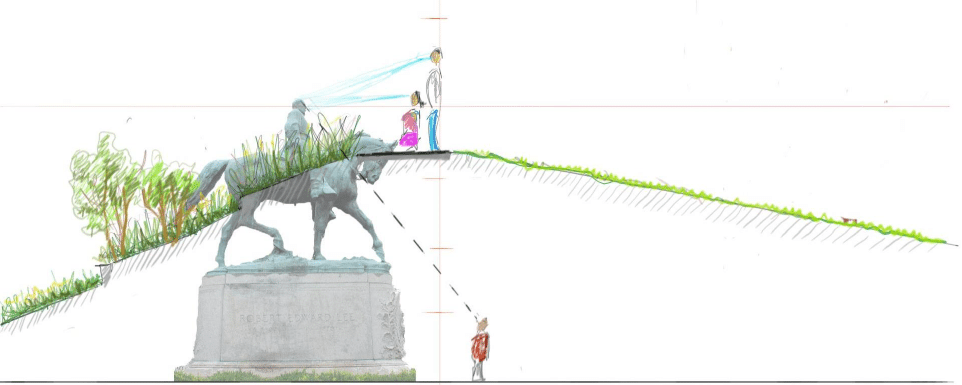

Image: Harriett Jameson Brooks

“I realized that if there are 1,500 symbols of the Confederacy on public property in the U.S., then there are 1,500 public places in our country that need to be redesigned, reimagined, and reconciled.”

Today there are 1,500 symbols of the Confederacy on publicly supported land in the U.S., including monuments, schools, parks, and roads. While many would see this as a barrier, Harriett considers it an opportunity. “It shook me as a landscape architect.” Harriett exclaims, “I realized that if there are 1,500 symbols of the Confederacy on public property in the U.S., then there are 1,500 public places in our country that need to be redesigned, reimagined, and reconciled.” With a desire to reclaim public space in the South and bring together communities, Harriett formed the Common Ground Collaborative. Through this initiative, she intends to work with communities to create public spaces that reflect their collective values.

While landscape architects are not typically at the forefront of these type of social issues, Harriett urges the importance of joining, if not leading, the conversation. In an effort to confront these types of complicated challenges and push past the existing limitations of the profession, Harriett pursued the LAF Fellowship for Leadership and Innovation. Designed to empower leaders and innovators in the profession, Harriett states that “each of this year’s fellows is finding a way to push back, to expand what it means to be a landscape architect, what types of problems we take on, and why we do the work that we do.” As one of four recipients of the 2017 LAF Fellowship, Harriett has spent the past year exploring ideas such as this that push landscape architects into the conversation and catalyze positive change.

In closing, Harriett proclaims, “I see the world that landscape architects can create when open ourselves to what is deeply personal, when we explore our periphery, and when we take hold of the future waiting to emerge.”

—

This video was filmed on September 28th, 2017 at ASLA’s Center for Landscape Architecture in Washington, DC as part of the Land8x8 Lighting Talks sponsored by Anova Furnishings.

![10 Billion Mouths [Video]](https://land8.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/michael-grove-land8x8-175x175.png)

![10 Billion Mouths [Video]](https://land8.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/michael-grove-land8x8-80x80.png)

![Deep Collaboration: Ecology, Research, Design [Video]](https://land8.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/stephanie-carlisle-175x175.png)

![Deep Collaboration: Ecology, Research, Design [Video]](https://land8.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/stephanie-carlisle-80x80.png)

![Workaround [Video]](https://land8.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/richard-jones-land8x8-175x175.png)

![Workaround [Video]](https://land8.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/richard-jones-land8x8-80x80.png)

![Beyond Our Landscapes: Interdisciplinary Research and Design for Health [Video]](https://land8.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/coco-alarcon-175x175.png)

![Beyond Our Landscapes: Interdisciplinary Research and Design for Health [Video]](https://land8.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/coco-alarcon-80x80.png)

![The Next Green Revolution [Video]](https://land8.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Thomas-Rainer-Land8x8-175x175.png)

![The Next Green Revolution [Video]](https://land8.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Thomas-Rainer-Land8x8-80x80.png)

![Transforming Tysons [Video]](https://land8.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/sp-land8x8-175x175.png)

![Transforming Tysons [Video]](https://land8.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/sp-land8x8-80x80.png)

![Rising from the Rubble: 1500 Design Challenges for the Emerging Future [Video]](https://land8.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/JAMESON-COVER-175x175.png)

![Rising from the Rubble: 1500 Design Challenges for the Emerging Future [Video]](https://land8.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/JAMESON-COVER-80x80.png)