Author: Land8: Landscape Architects Network

Why Lonsdale Street is a Role Model for Urban Projects Around the World

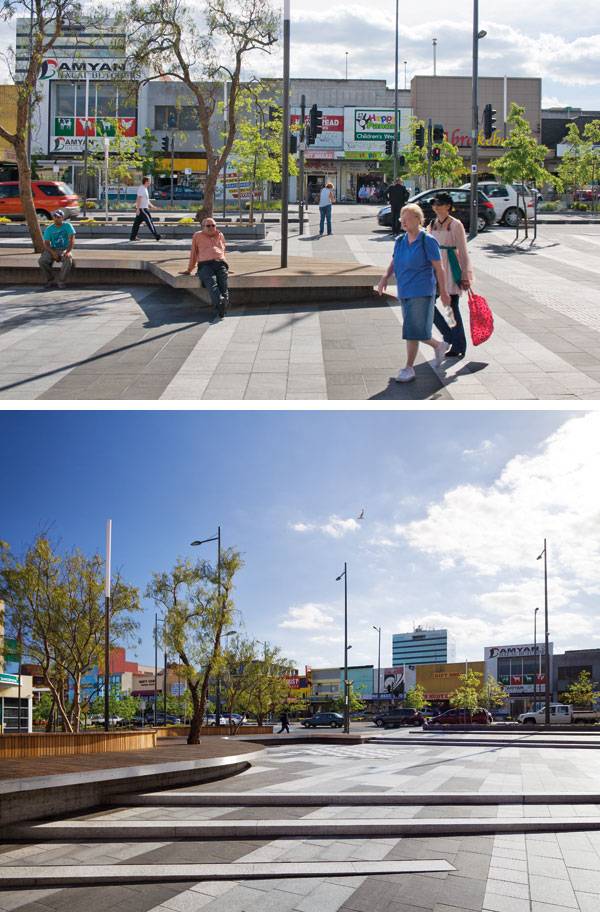

Lonsdale Street, by Taylor Cullity Lethlean Landscape and Urban Design and BKK Architects, in Melbourne, Australia. Modern cities with interesting architecture and good infrastructure still have problems with green spaces. We have noticed that public squares are sometimes underdone or misused. It happens everywhere, but what is the first step to change this situation? First and foremost we should study excellent urban projects. Doing this enables us to take a fresh look at the matter or even find inspiration. On the other hand, we are able to find solutions to urban problems, such as heavy vehicular traffic. Development of motorized transport has had a major impact on the shape of cities. Wide pavements are being replaced with parking and roads. However, when public squares focus on pedestrians instead of cars they can become examples of successful design. Lonsdale Street is a fine example of this much needed balance between ecology and human needs.

Lonsdale Street. Photo credit: John Gollings

Lonsdale Street

Premier Boulevard in Dandenong

This extraordinary project is located in one of the suburbs of Melbourne, Australia – Dandenong. It is a prosperous retail spine with many shops and a dynamic produce market situated here. So it makes this area a unique and significant space in the city. Due to the retail located here, there is also a lot of traffic congestion, which has had a strong impact on the shape of the boulevard.

Lonsdale Street. Photo credit: John Gollings

Lonsdale Street. Photo credit: John Gollings

The First Impression

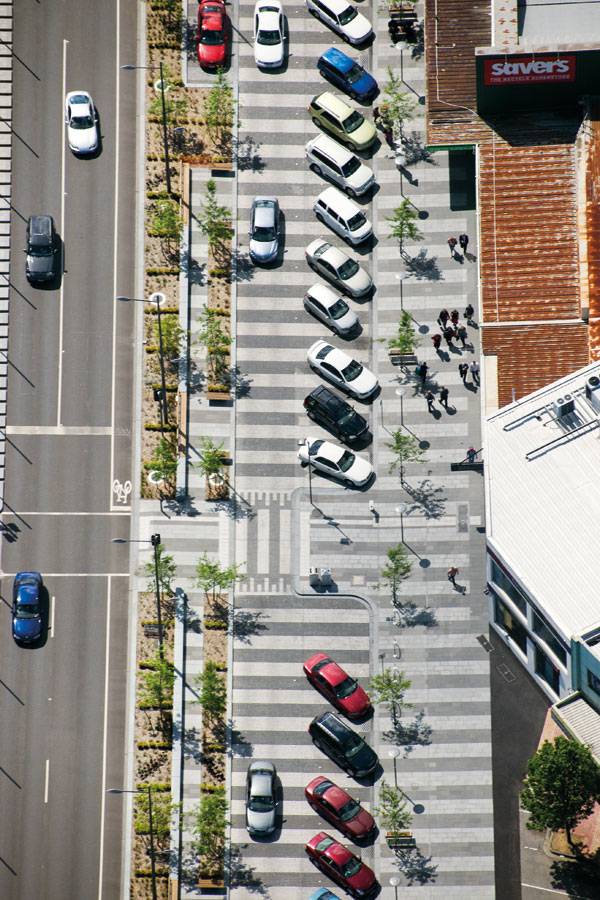

When we look at Lonsdale Street from a bird’s eye view, we can notice that nothing is random or unnecessary here. Parallel lines found in the flooring and more subtly in the long road, with two lines in each direction and a pedestrian area with parking are what catches the eye. A natural barrier – trees, divides these zones. They not only bring oxygen, but also create a secluded spot where people can rest or simply relax. This is what we notice first, but why is Lonsdale Street unique and very interesting for landscape architects?

Lonsdale Street. Photo credit: John Gollings

Focus on the Function

First and foremost, Lonsdale Street is a well-organized space. Vehicular traffic is considered and it is not disturbing to pedestrian movement. Therefore, it is no wonder that people from Dandenong simply love this place. They can comfortably park their cars, go shopping and then take a break in this amazing area. Wooden benches invite everyone to sit under pin oaks trees and low bushes help create the right atmosphere. The street is known for being a marvelous place, which certainly no one wants to leave.

Lonsdale Street. Photo credit: John Gollings

Ecology Meets Urbanization

On the other hand, the ecological aspect is also significant. Lonsdale Street is perceived as an environmentally friendly space. Not only does Dandenong’s public square produce oxygen, but it also saves the city a lot of money, which city authorities in other towns must spend on items such as water bills. How is this possible in a tremendous metropolis such as Melbourne? The answer is surprisingly simple, a linear garden along the length of Lonsdale Street is reusing storm water for irrigation purposes.

Lonsdale Street. Photo credit: John Gollings

Lonsdale Street by Night

Lonsdale Street is not only a great place to hang during the day, but also at night. If someone thinks that Lonsdale Street shuts down when the last shop closes – they would definitely be wrong. It is a lively place even in the evening. Vertical street lamps, designed by Electrolight in collaboration with Daniel Sequeira, line the street and glow in a rainbow of colors. These lights attract people’s attention and make Dandenong’s public square a special meeting point for townsfolk, at any time of the day. There is no getting around the fact that, in recent years Lonsdale Street has positively changed into a desirable place that everyone is talking about. For the first time in a long while, designers noticed vehicular traffic’s consequences and created a solution. This project is known for being well thought out and responding to the people’s needs, as well as ensuring a balance between the environment and architecture. People of Melbourne should be proud that one of the most captivating urban projects is situated in their city.

Lonsdale Street. Photo credit: John Gollings

Lonsdale Street. Photo credit: John Gollings

Lonsdale Street. Photo credit: John Gollings

Lonsdale Street. Photo credit: John Gollings

Full Project Credits for Meeting Bowls, by mmmm…

Landscape Architects: Taylor Cullity Lethlean Landscape and Urban Design Collaboration: BKK, Electrolight, Design Flow and David Sequeira Location: Dandenong, Victoria, Australia Size: 30,000m2 Completion Date: 2007- 2011 Client: Places Victoria Construction budget: $35,000,000 Project Team: Simon Knott, Perry Lethlean, Scott Adams, Lisa Howard, Noelle Teh, Lin Tan, Michael Roper, Michael White Project Management: Places Victoria Builder: Canteri Brothers Civil / Structural: Arup Civil (Langhorne Plaza): Argo Civil / Structural (Langhorne Plaza): KLM Lighting: Electrolight

Awards for Lonsdale Street:

2013 AIA National Architecture Awards, Winner Walter Burley Griffin Award for Urban Design 2013 AIA Victorian Architecture Awards, Winner Melbourne Prize 2013 AIA Victorian Architecture Awards, Winner Urban Design 2013 PIA Australia Award for Urban Design, Commendation 2012 AILA Awards, Excellence Award for Design in Landscape Architecture Recommended Reading

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

Article by Paulina Sawczuk

Malmö’s New Bustling Commuter Hub Moves 37,000 People a Day

St Johannesplan & The Konsthall Square, by White Arkitekter, in Malmö, Sweden. The coastal city of Malmö, located just a short train ride from the Danish capital of Copenhagen, is one of the most diverse and fastest growing cities in Sweden. The population includes a huge proportion of immigrants and young people, as well as thousands who commute to and from nearby Copenhagen for work and school each day. Its diversity, combined with its unusual location, makes Malmö one of Scandinavia’s most unique and vibrant cities.

Masterplan of St Johannesplan & The Konsthall Square, by White Arkitekter

St Johannesplan & The Konsthall Square

Moving 37,000 People a Day

Located outside of the main downtown district, Triangeln was a relatively quiet area until recently. With the completion of the new City Tunnel train connecting Malmö’s central station to Copenhagen via the Tranglen station, the area has been transformed into a bustling commuter hub. This radical change means that the Triangeln area is now accommodating upward of 37,000 commuters each day. As a result, the city needed to create a space that would both reflect and accommodate this change, while still complementing the existing community.

Johannesplan & The Konsthall Square . Photo credit: Hanns Joosten

One Project: Two Spaces

White Arkiteker’s design proposal was selected as the winner of an international design competition by the city to re-imagine the space around the Triangeln station. The design transforms this previously overlooked area into a bustling commuter hub and outdoor living area for locals. The project area can be divided into two main squares: Konsthalltorget and Sankt Johannesplan. Konsthalltorget is adjacent to the city’s art gallery (Malmö Konsthall) and the Triangeln shopping center. The gallery is one of the largest in Europe. It exhibits modern art from around the world and attracts 200,000 guests each year.

Johannesplan & The Konsthall Square. Photo credit: Hanns Joosten

Recommended Reading

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

As a significant stakeholder in the project, the art gallery was extremely involved in the design process, ensuring that the new space would function harmoniously with the gallery. The Konsthalltorget space acts as an extension of the art gallery, and was designed to complement and showcase the gallery’s unique and stunning architecture, as well as to host temporary outdoor exhibitions. The second part of the design, Sankt Johannesplan, is oriented toward St. Johannes Church. Built during the Art Nouveau period and also called the Church of Roses, the church is an important landmark in the city. Sankt Johannesplan is also the location of the new Triangeln station’s north entrance and acts as a hub for commuters.

Johannesplan & The Konsthall Square. Photo credit: Hanns Joosten

Johannesplan & The Konsthall Square. Photo credit: Hanns Joosten

Flexibility Was a major Factor in the Design Scheme

Round planters that double as benches, as well as some scattered perennial beds, add some green to the space. While more trees would be a welcome addition to brighten and break up the space, it was important that the design be flexible and adaptable to various types of events, as well as free of obstruction for busy commuters. A 30-square-meter area of water jets adds a certain playfulness to the space, and becomes a popular area for children during the summer months.

Johannesplan & The Konsthall Square. Photo credit: Hanns Joosten

Johannesplan & The Konsthall Square. Photo credit: Hanns Joosten

Robust Responsive Environment

Toward the center, an elevated concrete disk works well as a stage and display area during events and exhibitions, but also functions as seating for day-to-day use. At night, the illuminated platform, along with the rest of the nighttime lighting design, creates a lasting impression for passersby.

Johannesplan & The Konsthall Square. Photo credit: Hanns Joosten

The Glass Dome

The glass dome structure is the northern entrance to the Triangeln train station. Situated in the middle of the space, it acts not only as a station entrance, but as a stunning architectural feature for the square. Aside from the train station, several bus lines service the area, and bicycle parking has been provided onsite. The site’s design is complementary to the city’s shifting transportation policies, which focus on incorporating and facilitating public and active transport, rather than the use of private cars. Already, the square has become a popular place not only for commuters, but also for skateboarders, filmmakers, artists, and musicians — acting as a hub for not only transportation, but for recreation and culture.

Johannesplan & The Konsthall Square. Photo credit: Hanns Joosten

A Hub for Commuters — and for the Community

Malmö was already known globally for its innovative architecture and public realm, and White Arkitekter has elevated an overlooked area to a public living space and bustling commuter hub, accommodating more than 37,000 people a day. The combination of contemporary minimalist and ornate Art Nouveau styles gives the square a distinct and memorable feel that effortlessly complements its surroundings, while efficiently moving commuters. The site’s location supplies the space with a steady flow of people to animate it, from the bustling weekdays to lazy Sundays. While the primary purpose of the site is as a hub for the city’s thousands of daily commuters, and the open design of the square mitigates congestion and facilitates the efficient movement of people, its great location has also helped it to become one of Malmö’s newest local hangouts.

Johannesplan & The Konsthall Square. Photo credit: Hanns Joosten

Full Project Credits for St Johannesplan & The Konsthall Square

Project Name: Sankt Johannesplan and Konsthalltorget. (St Johannesplan & The Konsthall Square) Location: Malmö, Sweden Designers: White Arkitekter AB Team: Niels de Bruin, Anna Eklund, Gustav Jarlöv, Andreas Milsta (lighting design), Ebba Matz (artist) Date of Construction: 2014 Size: 28,000 sqm Client: City of Malmö and The Swedish Church Photographer: Hanns Joosten

Recommended Reading

- Natural Swimming Pools: Inspiration For Harmony With Nature by Michael Littlewood

- You Can Draw in 30 Days: The Fun, Easy Way to Learn to Draw in One Month or Less by Mark Kistler

Article by Michelle Biggs

Top 10 Ex-Industrial Sites Turned Into Stunning Landscapes

We take a look at 10 ex-industrial sites that experienced the powerful transformation of landscape architecture. Ex-industrial public parks are a shining example of how great design can reuse, repurpose, and reintegrate spaces for the public. Innovations in urban ecology, water treatment, and green urban infrastructure have all been made, thanks to the unique challenges provided by these landscapes. They have challenged us aesthetically, as well, to find value and beauty in the industrial heritage of a site, asking us to widen the scope of what we consider to be beautiful and worthwhile.

Here are 10 ex-industrial sites that resulted in innovative and stunning landscapes:

10. Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, London, England

Home to the 2012 Olympic and Para-Olympic Games, the 560-acre Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park is one of the largest on this list. Once an industrial area and dumping ground in London’s east end, the park was quickly and expensively transformed in order to host the games. The cleanup of the site alone cost 200,000,000GBP. Two hundred and fifty acres have been transformed into woodlands and wetlands, providing habitat as well as river flood protection for surrounding areas. Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park is continuing to grow and change, intending to become a new cultural center and neighborhood as well as greenspace and animal habitat. Many of the Olympic buildings are being replaced by housing and some commercial buildings. WATCH: A walk in London’s new Olympic Park

9. Klyde Warren Park, Houston, Texas, USA

Klyde Warren Park is unique on this list since it isn’t a park that replaced an industrial site, but one that provides a unique solution to a similar problem. The park is on a “deck” covering a working freeway, making the thoroughfare subterranean and creating a continuous physical and visible connection through the city. The design is meant to encourage discovery, while also providing a relationship between Uptown and the Dallas Arts District. WATCH: A Day in the Life of Klyde Warren Park – Flyover

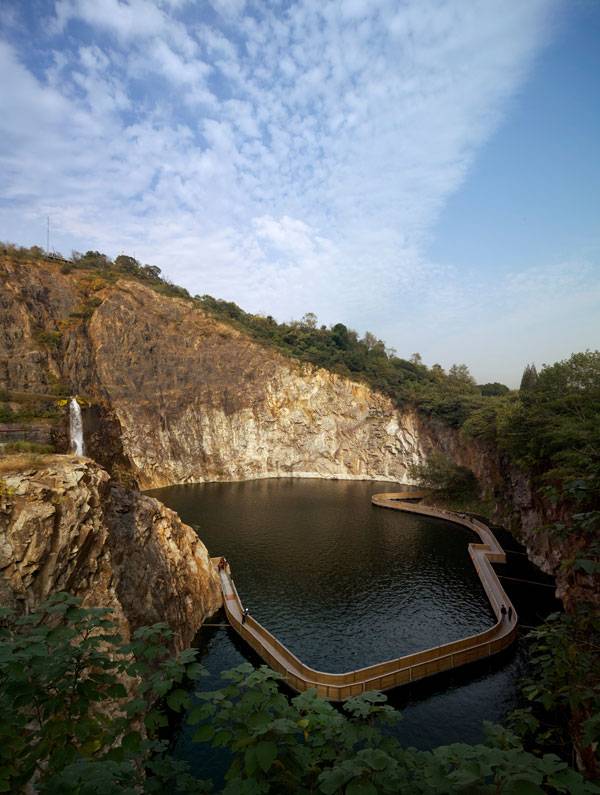

8. Quarry Garden, Shanghai, China

The Quarry Garden is located in the Shanghai Chen Botanical Garden, the largest botanical garden in Shanghai. From the 1950s to the 1980s, the site was a functioning quarry, doing massive damage to the Chen Mountain, leaching and removing soils and vegetation and destroying habitat. The design re-creates an ecologically functioning landscape that doesn’t try to hide the site’s history. The materials palette recalls both the natural and industrial pasts, using rusted steel and concrete as well as stone and vegetation to lead visitors into the quarry basins.

Quarry Garden in Shanghai Botanical Garden. Photography credit: Yao Chen

7. Hunter’s Point South Waterfront Park, Queens, New York, USA

The site that now houses Hunter’s Point Park was for a long time an abandoned post-industrial landscape with a breathtaking view of Manhattan. The park is a part of a large, affordable housing project and will provide recreational greenspace for thousands of new residents. It features a large, oval lawn space, a dog park, concession buildings, and ecological wetlands. Hunter’s Point is one of many projects in the works intended to provide public access to New York City waterfronts by creating accessible greenspace, trails, habitat, and gathering spaces.

Planting at Hunter’s Point South Park. Photo credit: Wade Zimmerman

6. Olympic Sculpture Park, Seattle, Washington, USA

Built in 2007, the Olympic Sculpture Park is an extension of the Seattle Art Museum. The seven-acre site is home to temporary and permanent art installations. The site was owned by the Unocal Corp. from 1910 to 1975, housing a fuel facility, and was in cleanup for another 10 years after operations ceased. Funds to buy the land were raised by the Seattle Art Museum and the Trust for Public Land, eliciting thousands of donations for the Sculpture Park. The design of the park is based off western Washington’s topography and native vegetation. The planting palette starts with a cascade of mountain plants on the highest part of the site, shifting as the topography changes down past the water’s edge into Puget Sound, where habitat reconstruction provides the only salmon habitat on the Seattle waterfront.

Recommended Reading

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

Cader’s Eagle at Olympic Sculpture Park. Photo credit: SounderBruce. Licensed under CC 2.0. Flickr

5. Sugar Beach, Toronto, Canada

Sugar Beach is on the banks of Lake Ontario, in a very urban area surrounded by buildings and industry. The park provides not just a repose from the city, but a sugar-coated confection in the middle of it all. Inspired by a nearby sugar factory, the design evokes old-school candy imagery with bubblegum pink umbrellas, candy-striped boulders, and an illuminated water feature, making the park nearly Wonka-esque.

Sugar Beach; credit: www.claudecormier.com

4. Gasworks Park, Seattle, Washington, USA, by Rich Haag

Gasworks Park was the site of a gas plant from 1906 to 1956, a serious source of pollution and a point of frustration and anger for the surrounding community of Wallingford. When the site was acquired by the city for a park in 1965, landscape architect Rich Haag’s intention to leave some of the plant’s towers as valuable and historical point of interest was controversial. Haag fought to keep the industrial past visible, while also designing more traditional sweeping lawns, a viewpoint hill, and wooded screens. Now, despite Gaswork’s rocky past, it is a beloved public gathering space and one of the most visible green spaces in Seattle. WATCH: KCTS 9 – History Making: Lake Union Stories

3. Shanghai Houtan Park, Shanghai, China, by Turenscape

Shanghai Houtan Park is an exceptional example of designing landscapes to be functional, living landscapes. The site on the Huangpu River is long and narrow, following the river bank. It was once a brownfield, having hosted a steel mill, shipyard, and landfill. The design intent was to create a beautiful, safe place for visitors, to clean the river water, and to prevent flooding. This was accomplished by constructing a mile-long wetland through the park that cleans water from the very polluted river. Related Articles:

- Transforming a Coal Mining Site into a Cultural Hub

- Offenbacher Hafen Turns from Polluted Industrial Port to Ecological Riverfront

- Top 10 Reused Industrial Landscapes

The wetland plants and soils remove nutrients, while a series of terraces adds oxygen to the hypoxic water. According to the American Association of Landscape Architects, the constructed wetlands can treat up to 500,000 gallons of polluted water per day. Visitors to the park can experience a safe and close connection to the water and plants in the wetland. They are encouraged to explore the wetland as a landscape feature and also as a functioning system.

Shanghai Houtan Park. Photo credit: Turenscape

2. C-m!ne, Genk, Belgium

The C-mine plaza in Genk pays homage to its mining-town past while launching the urban plaza into the future. Materials were chosen for their aesthetic similarity to the coal produced by the mine and were made out of a waste product from the mining process. Buildings surrounding the square were mostly all mining buildings that now house elements of the cultural hub of the city. The square is vivacious, with a bright lighting design through the square and up the shaft tower that dominates the flat landscape. Its flatness is intended to make the square multi-functional and able to hold many people during large events.

GENK C-m!ne by Hosper in Genk, Belgium

1. SteelStacks Campus, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, USA

SteelStacks is a public park, cultural hub, and entertainment venue in what was once a Bethlehem Steel plant. Bethlehem Steel used to be the second-largest producer of steel in the United States, imprinting itself on the lives of the Bethlehem community. When the plant shut down in the 1990s, the people of Bethlehem rallied to have it conserved, saving the iconic structures and incorporating them into the campus. The blast furnaces from the plant still stand behind the Levitt pavilion, which is dramatically uplit at night, while the visitor center in the plant’s stock house was opened in 2012.

SWA Group design Sands Bethwork at Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, USA. Photo credit: Tom Fox

Recommended Reading

- Natural Swimming Pools: Inspiration For Harmony With Nature by Michael Littlewood

- You Can Draw in 30 Days: The Fun, Easy Way to Learn to Draw in One Month or Less by Mark Kistler

Article by Caitlin Lockhart

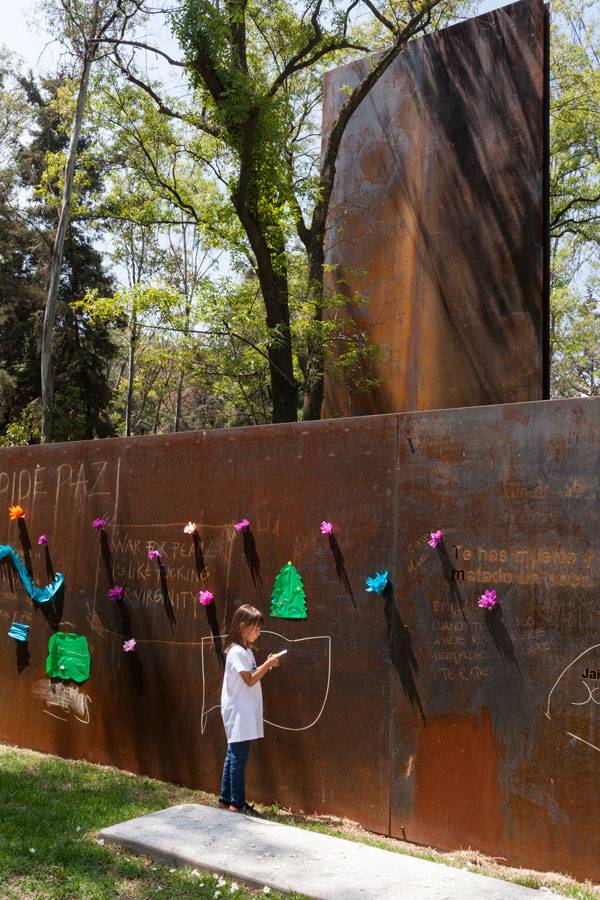

Landscape Storytelling – Memorial to Victims of Violence

Memorial to Victims of Violence, by Gaeta-Springall Arquitectos, Mexico City, Mexico. The power and importance of storytelling is a largely unrecognized force in landscape architecture. But it can be used to bring people together, learn about each other, and exchange experiences. Not all stories are easy to tell, however, and stories about violence might be some of the most unpleasant. Why would someone want to hear or tell stories about violence? How can such stories be told? Violence is one of the most important issues facing Mexico City, where it plays a role in Mexican society and in the daily life of the city’s people. Violence in the city has to be processed and discussed. Gaeta-Springall Arquitectos chose to address this theme by telling a story through a successful landscape design in Chapultepec Park, an enormous park that reminds us of Central Park in New York City.

Memorial to Victims of Violence in Mexico, by Gaeta Springall Architects Taken in Year: 2015. Photo credit: Sandra Pereznieto.

Memorial to Victims of Violence

In addition to a zoo, a castle, an anthropology museum, and areas for walking, jogging, and cycling, the park is home to the Memorial to Victims of Violence. The memorial provides an opportunity to continue the open story about victims of violence while interacting with other people and with nature.

Memorial to Victims of Violence in Mexico, by Gaeta Springall Architects. Taken in Year: 2013. Photo credit: Sandra Pereznieto.

Memorial to Victims of Violence in Mexico, by Gaeta Springall Architects. Taken in Year: 2013. Photo credit: Sandra Pereznieto.

Recommended Reading

- Natural Swimming Pools: Inspiration For Harmony With Nature by Michael Littlewood

- You Can Draw in 30 Days: The Fun, Easy Way to Learn to Draw in One Month or Less by Mark Kistler

Let’s figure out the meaning of the Memorial to Victims of Violence by taking a look at some of the components of a classical story: the plot, the characters, the setting, the conflict, and the resolution.

Memorial to Victims of Violence in Mexico, by Gaeta Springall Architects Taken in Year: 2013. Photo credit: Sandra Pereznieto.

The Story of “Memorial to Victims of Violence”

The Plot

On a 15,000-square-meter site, three main elements – steel, water, and light – were assembled to form the plot of the story. The steel is present through 70 wall surfaces, both rusty and mirroring. Consequently, the suggestion of violence can be seen in two dimensions: the void created between the steel walls and trees that evokes the absence of the victims; and the build — the surfaces of the steel walls themselves.

Memorial to Victims of Violence in Mexico, by Gaeta Springall ArchitectsTaken in Year: 2015. Photo credit: Sandra Pereznieto.

Memorial to Victims of Violence in Mexico, by Gaeta Springall Architects . Taken in Year: 2015. Photo credit: Sandra Pereznieto.

Memorial to Victims of Violence in Mexico, by Gaeta Springall Architects. Taken in Year: 2013. Photo credit: Sandra Pereznieto.

The Characters

Good stories don’t just have a good plot; their impact lies in how the plot is accepted by relevant actors. The most significant feature of the rusted steel slabs is that people can write on them with chalk. The created interaction allows interior voices to be heard. In this way, different people have the chance to leave a conglomeration of messages – to the loved, to violence, to political slogans, etc.

A Chance to Process Your Own Memories

Present in a metaphorical way, the main character is represented by the many victims of violence, who are the reason for this landscape design project. Even if the main character has an important role, Gaeta-Springall Arquitectos expands the presented importance on the people strolling through the memorial by giving them the chance to process their memories or to share feelings and emotions with other people.

More Top Articles on LAN

- 10 of the Most Common Mistakes People Make in Planting Design and How to Avoid Them

- Interested But Not Confident? – Know How to be Good at Hand Drawings

- Top 10 YouTube Tutorials for Technical Drawing

Memorial to Victims of Violence in Mexico, by Gaeta Springall Architects. Taken in Year: 2013. Photo credit: Sandra Pereznieto.

The Setting and the Conflict

Located in the most important park of Mexico City – Bosque de Chapultepec – the story about the victims of violence is also elevated in importance. At more than 686 hectare, Bosque de Chapultepec is one of the largest city parks in the Western Hemisphere. With this project, 15,000 square meters of public space was recuperated from the forest belonging to the federal government.

Memorial to Victims of Violence in Mexico, by Gaeta Springall Architects. Taken in Year: 2013. Photo credit: Sandra Pereznieto.

Memorial to Victims of Violence in Mexico, by Gaeta Springall Architects. Taken in Year: 2015. Photo credit: Sandra Pereznieto.

The Resolution

The project plays the double role of public space and memorial, a feature that makes it more successful and beloved. Gaeta-Springall Arquitectos addresses one of the most important issues of contemporary Mexican society — violence – through a story. The resolution is that everyone has access to this “landscape design story” by the use of different elements and interactions. Thus, this memorial is a powerful study in storytelling. Nevertheless a question remains: How can such projects of storytelling in landscape design be multiplied?

Memorial to Victims of Violence in Mexico, by Gaeta Springall Architects. Taken in Year: 2013. Photo credit: Sandra Pereznieto.

Full Project Credits for Memorial to Victims of Violence

Project name: Memorial to Victims of Violence in Mexico Completion date: April, 2013 Location: Mexico City (Mexico) Designer: Gaeta Springall Architects (Julio Gaeta / Luby Springall) Photographer: Sandra Pereznieto Area: 15,000 m2 Show on Google Maps

Recommended Reading

- Natural Swimming Pools: Inspiration For Harmony With Nature by Michael Littlewood

- You Can Draw in 30 Days: The Fun, Easy Way to Learn to Draw in One Month or Less by Mark Kistler

Article by Ruth Coman

13 Years to Create the Dream of Martin Luther King Park

Martin Luther King Park, by Atelier Jacqueline Osty & associés., in Paris, France. One of the most important things in landscape architecture design is making a clear assessment that can be accessible in the future. The method to get a successful result is to divide a proposal into parts in order to develop it stage by stage, providing a visualized target. Once the proposal is phased in years, it is easier for us to estimate the future situation as precisely as possible. Here is an excellent example that tells us how to process a project in phases and what we should take into account when designing in this way.

Martin Luther King Park. Photo credit: Martin Argyroglo

Martin Luther King Park

Martin Luther King Park is located in the Clichy Batignolles area of Paris, which was chosen to host the Olympic Village as part of the city’s bid for the 2012 Olympics. The whole project was planned by a team that consisted of town planners, landscape architects, and engineers. The park and new districts have been built upon an old railway platform and storage place. The project has kept most of the main structural lines. It is said that 6,500 new habitats and 12,700 employees will move into this area in the future. The park has been designed mainly in two phases. The whole process from proposal to a finished project will take more than 13 years.

Martin Luther King Park. Photo credit: Dubois Fresney

Phase One

The whole area is 45 hectares, which includes the 10-hectare park. The first phase was built between 2003 and 2007. It was started from the east side of the project, where high-density districts already exist, so the park offers a leisure space for the many people who live nearby.

More Top Articles on LAN

- 10 of the Most Common Mistakes People Make in Planting Design and How to Avoid Them

- Interested But Not Confident? – Know How to be Good at Hand Drawings

- Top 10 YouTube Tutorials for Technical Drawing

Martin Luther King Park. Photo credit: Dubois Fresney

Phase Two

The second phase is divided into two parts. The first part was built between 2008 and 2014. It extends to the northwest side of area. In this part, the concentration is on the park, not buildings. The second part includes the new districts in the northeast and southwest quadrants. They are expected to be complete in 2016.

Recommended Reading

- Natural Swimming Pools: Inspiration For Harmony With Nature by Michael Littlewood

- You Can Draw in 30 Days: The Fun, Easy Way to Learn to Draw in One Month or Less by Mark Kistler

Martin Luther King Park. Photo credit: Martin Argyroglo

Sustainable Water System

The park contains various water features that express different senses of nature. The center of the park is an open water feature consisting of four biotope basins supplied with non-potable water. Ditches are planned along walkways to show wetland vegetation and also collect rainwater and move it to underground storage to supply water for the park.

Martin Luther King Park. Photo credit: Martin Argyroglo

The Clever Use of the Wind Turbine

A dry fountain is designed as an attractive square for summer activities. All of these water features are built as a whole system. One remarkable feature is the use of a wind turbine for re-circulating the water from the planned ditch.

Diversifying Spaces for Various Activities

From southeast to northwest, the park includes various spaces for different activities. Each part of the park has a specific character to match to its function. A playground, skate park, and sports fields are supplied for fitness. In the center of the park, the biotope basins provide an open park view and a habitat for wildlife. The lawn and woods offer a perfect place for daily relaxing.

Martin Luther King Park. Photo credit: Martin Argyroglo

Green Connection

Most times, offices and houses are planned first, then the green space is developed. In this case, the park has been planned first due to technical reasons. This turns out to be good for landscape architects, who can then shape the green space with fewer limitations.

The Green Connecting Arms of Ecology

Green corridors as “arms” of the park extend into both the eastern and western sections of the project and insert themselves into office buildings and the housing district. At the same time, the corridors also increase a connection between the park and others surrounding urban green spaces.

More Top Articles on LAN

- 10 of the Most Common Mistakes People Make in Planting Design and How to Avoid Them

- Interested But Not Confident? – Know How to be Good at Hand Drawings

- Top 10 YouTube Tutorials for Technical Drawing

Seasonal change on display at Martin Luther King Park. Photo credits: Dubois Fresney

Martin Luther King Park. Photo credit: Martin Argyroglo

There are a few reasons why this park is successful.

First: It has a clear, phased proposal that helps designers to understand the full project’s distinct direction. Second: The landscape architecture was considered at the beginning of the planning process. This provides a priority for the designers to emphasise the urban green connection, so that the building district and the park can have a seamless connection without wasteland.

Martin Luther King Park. Photo credit: Martin Argyroglo

Martin Luther King Park. Photo credit: Dubois Fresney

Third: Sustainability comes into play, including the use of natural energy such as solar and wind and the reuse of collected rainwater. This reduces the cost of maintenance. Fourth: Different water features and various vegetations provide biodiversity in the park to make it livelier. The park also brings residents closer to nature, even though they live in the city. What do you think makes an urban park successful?

Martin Luther King Park. Photo credit: Martin Argyroglo

Full Project Credits for Martin Luther King Park

Project Name: Martin Luther King Park Programme: Design of an urban park in the Clichy-Batignolles district of Paris Location: Paris, France Project Team: Jacqueline Osty, landscape architect; Jérôme Saint-Chély (first phase); Daniela Correia with Fanny Sire (second phase) In association with: François Grether, urban architect. Concepto, lighting concept, OGI, civil engineers Budget: First phase — 14, 9 M € HT ; second phase — 30,8 M € HT Size: 10 hectares: 4, 4 hectares (first phase); 5, 7 hectares (second phase) Design dates: from 2005 to 2006 (first phase) from 2008 to 2011 (second phase) Realisation: 2007 (first phase) 2012 to 2014 (second phase first part) Approx.2017- 2020 (second phase second part) Commissioned by: City of Paris – DEVE of Paris (Direction des Espaces Verts et de l’Environnement) (Direction of Green Spaces and Environment) Show on Google Maps

Recommended Reading

- Natural Swimming Pools: Inspiration For Harmony With Nature by Michael Littlewood

- You Can Draw in 30 Days: The Fun, Easy Way to Learn to Draw in One Month or Less by Mark Kistler

Article by Jun Yang

Hill Squares Gets Much Needed Makeover, Spinning it in to the 21st Century

Hill Square, by Buro Sant en Co Landscape Architecture, Tilburg, The Netherlands. Tilburg is a thriving Dutch city with an extremely diverse population, including almost one-quarter of foreign descent, as well as being home to many students. Historically speaking, the Hill has long been one of the most important public squares in the city, serving as a landmark and gathering area for locals. However, over the years, the square has been slowly becoming less and less relevant, as a rapidly changing population dynamic has transformed the needs of residents. Ultimately, this diverse and evolving community needed a new space, one that still offered the functions of a traditional public square, but which also could address some new needs.

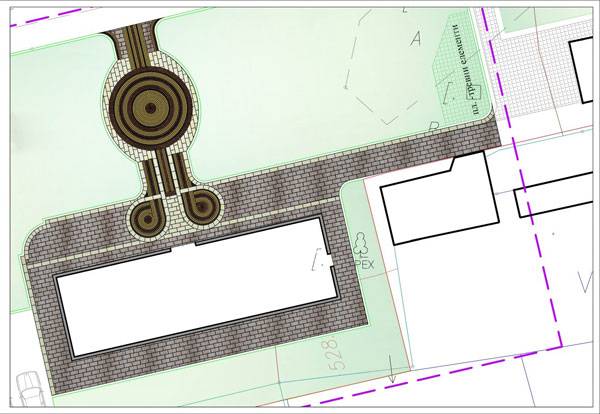

Masterplan of the Hill Square. Image courtesy of Buro Sant en Co Landscape Architecture

Hill Square

A Refreshing Change: The Oasis in the City

Dutch Landscape Architecture firm Buro Sant en Co was chosen by means of a design competition that called for proposals to bring Hill Square into the 21st century. The first round of the competition involved selection by a professional jury, then from among these nominees, locals were invited to vote for their favorite design.

Recommended Reading

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

The firm’s proposal went on to win the competition, receiving over 50% of the public votes and proving the be the clear favorite among the community.

Masterplan of the Hill Sqaure. Image courtesy of Buro Sant en Co Landscape Architecture

The Main Goal

The firm’s goal was to maintain and preserve the city’s heritage by restoring the square to its former glory, while also creating a modern and memorable new space. Buro Sant en Co envisioned the primary functions of the design as relaxation and community — in the designers’ own words, “an urban oasis.”

Visualization of the Hill Square. Image courtesy of Buro Sant en Co Landscape Architecture

Simple But Elegant Design Solution

Buro Sant en Co’s design solution is simple but elegant. Lined with lime trees, the square is open and airy. At the square’s center, a simple platform that seems to almost float just above street level functions as a stage and venue for local events and festivals. The edge of this platform also doubles as seating for a street-side view.

More Top Articles on LAN

- 10 of the Most Common Mistakes People Make in Planting Design and How to Avoid Them

- Interested But Not Confident? – Know How to be Good at Hand Drawings

- Top 10 YouTube Tutorials for Technical Drawing

Hill Square. Image courtesy of Buro Sant en Co Landscape Architecture

Who’s Taking Advantage of the New Space?

The space is also being taken advantage of by local businesses such as restaurants, which make the most of the space during the summer months by setting out tables and umbrellas to create patio seating for customers.

Umbrellas out at Hill Sqaure. Image courtesy of Buro Sant en Co Landscape Architecture

The Grass Strips

Alternating strips of multicolored basalt and grass create a lasting visual impression. In the summer, the grass is watered by sprayers that also provide a cooling effect and create ambient sound, making the space more inviting to visitors.

Hill Square. Image courtesy of Buro Sant en Co Landscape Architecture

The Feeling of an Urban Oasis

Water jets also animate the space, inviting children and adults alike to play and contributing to the feeling of an urban oasis. Small details in materials and furnishings also add special character to the site. For example, the drainage includes custom grates with a beautiful leaf design.

The drainage includes custom grates with a beautiful leaf design. Image courtesy of Buro Sant en Co Landscape Architecture

From Day to Night

The site is usable 24 hours a day, and its transition from day to night is striking. Lighting was an especially important consideration in the square’s new design. Knowing that the square is in the city’s downtown and at the center of local nightlife, it was essential to make the space not only safe and secure to passers-through, but to create a lively and inviting nighttime atmosphere. When the sun goes down, the jets of water that act as a playground by day are lit up, turning them into dancing beams of light. Moving and changing constantly, the jets create a playful evening atmosphere. From underneath the stage area, recessed lighting illuminates the platform, adding to the illusion of its floating.

Hill Sqaure. Image courtesy of Buro Sant en Co Landscape Architecture

More Top Articles on LAN

- 10 of the Most Common Mistakes People Make in Planting Design and How to Avoid Them

- Interested But Not Confident? – Know How to be Good at Hand Drawings

- Top 10 YouTube Tutorials for Technical Drawing

But Is It a Green Oasis?

Buro Sant en Co describes its vision as a green oasis in the city. But there are only a few trees and some strips of turf on the site — hardly a green oasis. While the stage is slightly elevated above street level, without many trees, there is little else to provide some much needed vertical interest. From close enough, the contrast between the strips of paving and turf certainly adds dynamism, but ultimately the square is pretty flat. Without any people in it, there is hardly anything to animate the space from a distance.

Hill Sqaure. Image courtesy of Buro Sant en Co Landscape Architecture

Oasis in the Summer, Desert in the Winter

In fact, the site seems to work very well in the summer months, but how does it work in the winter? While the design indeed addresses the day-to-night transition elegantly, it in unclear how the space will successfully transition from the hot summer months to the wintertime. Without summer events and water features animating the space, the site may spend a large part of the winter months empty. It will be interesting to see how this urban oasis is adapted to the colder months.

Hill Sqaure. Image courtesy of Buro Sant en Co Landscape Architecture

A Breath of Fresh Air

Despite it shortcomings, the design for Hill Square is a much needed breath of fresh air for the city. The firm set out to create a space that could host summer events, as well as encourage relaxation. From an aesthetic point of view, the new square is quite striking, and with its interplay among green space, light, and water, Hill Square certainly feels like a summer oasis in the city. The problem of transitioning public space programming through the different seasons is a common one for designers. What are some projects where this transition has been executed masterfully, and why are they so successful?

Full Project Credits for Hill Square

Project Name: Hill Square Location: The Hill, Tilburg, Netherlands Designers: Buro Sant en Co Landscape Architecture Size: 3 Hectares Date of Construction: 2009 Client: Municipality of Tilburg Show on Google Maps

Recommended Reading

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

Article by Michelle Biggs

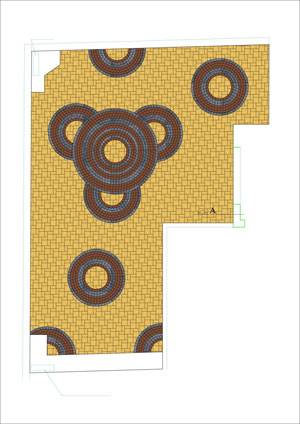

8 Common Mistakes People Make When Specifying Paving, and How to Avoid Them

In this article, we go into the eight most common mistakes people make when specifying paving and offer creative ways to avoid them. Have you ever wondered how you know where to go in the park? We’re not talking about the well-known places where you can walk with your eyes shut. We want to direct your attention to the cases in which you don’t know which way to go, but somehow find the right direction. Our challenge to you is this: How do you do that? Is it because of your sixth sense? Or is it because the path network is designed in a logical way? Alleys, platforms, and their pavements are fundamental elements of composition in landscape architecture. Their design is the skeleton of the overall landscape and serves as a basis that has a crucial effect on the final result. Designing your path network is very much like 3-D modeling. If your polygonal model isn’t excellent, you know that the whole scene will be a disaster in the end. And vice versa – if you take time to plan your base, everything else will follow and upgrade your initial idea so that it flows. Now that you understand the importance of paving, we invite you to walk with us to discover the eight mistakes to avoid if you want to be a better landscape architect.

1. Discounting the Proportion Between Green and Paved Areas

The first thing you need to do is to determine the right correlation between paved and green areas. Regulatory requirements vary from country to country, but when the green area percentage is set as a minimum, don’t settle for that minimum as the only possible solution. Expanding green areas will make for a much higher ecological, economic, and social quality of life. Of course, the proportion depends mainly on the site’s function. However, designers shouldn’t forget that path and pavement design isn’t the only manner in which composition and patterns can be defined. How to avoid planning too large areas of pavement? Think of more creative ways to achieve appealing projects. Shapes and colors can be found in both the hardscape and the softscape, so use them all. Below: Here is a good example displaying a well-balanced composition. Note how different levels and vegetation are used to add motifs to the plan.

Recommended Reading

- Landscape Paving Ifengspace Huanan

- Landscape Construction by David Sauter

Photo credit: Asnières Residential Park by Espace Libre Paysage et urbanisme

Baan Ladprao private residence. Photo courtesy of Landscape Architects 49 Ltd.

2. Disregarding paving’s future function when specifying it

Another top mistake designers make when specifying paving is forgetting paving’s main function. The purpose of alleys is to provide transportation and pedestrian communications. That’s why the future exploitation of the paved surface has the greatest importance when specifying paving. Depending on whether it is a small private yard or a vast public square, the stream of people varies. The pressure exerted on the surface is different, as well. The bearing capacity of pavement determines what materials we choose and how thick this surface layer should be. A comparison between two projects of such opposite uses of flooring can be found in the two following articles below. The first one offers an outstanding private garden design. The load that the pavement will have to bear is expected to be minimal. In this case, wood decking and stepping stones set in gravel are an appropriate design solution, as their bearing capacity doesn’t have to be big.

Modern Meets Mediterranean in an Outstanding Private Garden Design. Photo credit: Iúri Chagas

Recommended Reading

- Landscape Paving Ifengspace Huanan

- Landscape Construction by David Sauter

3. Not considering the importance of construction

A serious mistake is also made when it comes to specifying the layers of pavement construction. Concrete paving stones, decking, natural rock blocks, etc., compose only the upper surface layer of flooring. The other two main components of pavement are its substructure (or foundation) and ground foundation. The correct planning of pavement construction and the proper selection of input materials determine pavement’s expedience and durability. Foundation is the constructive element that allots pavement’s bearing capacity to the greatest extent. So how do we remember the significance of construction? Do you remember what we said about 3-d modeling? A well designed base is always the priority. Keep that in mind.

WATCH: How to prepare a paver base

4. Ignorance of pavement’s technical specifications

We’ve come to mistake number four – ignorance of pavement’s characteristics. You know that the variety of ornamental pavement on the market is enormous and continues to expand. Natural stone slabs, for example, differ in technical properties and durability according to their geophysical origin and structure. At the beginning of the design process, designers pick out a certain type of slab because of its hue, texture, or grit. In order to avoid possible problems, they need to know how the material corresponds to pressure, withstands chemical attacks, and whether it is durable. Did you know, for example, that resistance to cold is the most momentous technical specification of natural stone slabs? Concrete slabs, on the other hand, have different strengths and weaknesses. Permeable and cool pavements are also relatively new products, standing out for their unique improved properties, such as permeability, thermal emittance, and heat convection. More information about smart pavement can be found here:

So how can you avoid making this mistake? Consult with paving specialists and manufacturers. They are the experts who can answer all of your questions. They know what’s new and efficient on the market. Sometimes all you need to do is just ask.

5. Forgetting about the aesthetic functions of paving

So far, we have talked about the practical, technical aspects of pavement. But oftentimes — especially when we talk about pedestrian paths — the visual effect of ornamental paving is also important.

Paving detail courtesy of Milen Neshev – Landscape architect working for paving firm – Semmelrock Stein + Design.

Place d’Youville. Photo courtesy of Claude Cormier + Associés.

6. Ignoring paving installation schemes’ functions

Encroaching deeper into the subject of visual and aesthetic effects, we will put stress on the theoretical approaches that every landscape architecture student has studied, but almost every landscape architect leaves behind.

Paving detail courtesy of Milen Neshev – Landscape architect working for paving firm – Semmelrock Stein + Design.

Borås Textile Fashion Center. Photo courtesy of Thorbjörn Andersson

7. Not knowing how to combine different materials

Paving detail courtesy of Milen Neshev – Landscape architect working for paving firm – Semmelrock Stein + Design.

Coyoacán Corporate Campus. Photo courtesy of DLC Architects

8. No attention to detail

Finally, we have reached the last step on our walk of mistakes – no attention to detail. You have heard the expression “the devil is in the details”, and perhaps every landscape architect can grasp the meaning of it. When referring that saying to pavement design, attention should be paid to key features such as edging, surface inclination, equipment for surface drainage, and drainage construction of pavements and their basis. Edging, for instance, is important not only for the aesthetically beautiful effect of ornamental pavement, but mostly for supporting and protecting the construction. Even the design of valleys matters, so don’t make short work at the end. How to beat this final mistake? Although perfection is an abstract and imaginary concept, the desire to reach it drives people forward. And even if it is unattainable, we can at least try to get as close as possible. That’s how we will make the most of our work. Aren’t details the nostrum? How close to perfection do you think the paving design in this project is?

Central Plaza in Chiang Rai by shma.

How to Avoid All of These Mistakes

Coming to the end of our walk, it is time to consider whether there is a way to avoid all of these mistakes. It may sound quite cheesy, but my personal opinion is simple: We have to make all of these mistakes once to avoid repeating them in the future. What is your opinion on the matter?

Paving detail courtesy of Milen Neshev – Landscape architect working for paving firm – Semmelrock Stein + Design.

Recommended Reading

- Landscape Paving Ifengspace Huanan

- Landscape Construction by David Sauter

Article by Velislava Valcheva Return to Homepage

How to Learn From a Regional Garden Show – Stadtpark Papenburg

Stadtpark Papenburg, by RMP Landschaftsarchitekten, Papenburg, Germany. Have you asked yourself what a garden show is or what the transformative effects of it are? Since becoming popular in Germany and Austria in the 1980s, garden shows have aimed to improve the quality of life and the urban climate of cities. They also work toward regional-political development objectives. Regional garden shows are developed on disadvantaged sites, transforming them into attractive and pleasant locations. RMP Landscape Architects have extended the benefits and advantages of a regional garden show into a functional adaptation to meet the current requirements of the city park in Papenburg, Germany. Embedded in a larger context of city development, the implemented regional garden show in Stadtpark Papenburg is also a method of urban marketing, increasing the publicity and level of awareness of the city. Let’s see how these elements – regional garden show, urban marketing, and landscape design – interact in a single city park and how we can learn from such opportunities.

Masterplan of Stadtpark Papenburg. Image credit: RMP Stephan Lenzen Landschaftsarchitekten

Winds of Change – Stadtpark Papenburg

Located in the northwest section of Papenburg neighboring a shopping center, detached housing estates, and free fields, the city park has had to deal with the signature of nearly inconspicuous transit space. Where the shopping mall hides public activity and urbanity behind walls and detached houses preserve private leisure space, Stadtpark Papenburg has managed to evolve into an attractive and pleasant location. The park introduces a successful combination between new landscape elements and former structures in a city with maritime flair. (Papenburg is not only a center for shipbuilding, but also a center for flowers and horticulture – 35 M herbaceous plants and 25 M cucumber grow in Papenburg in a year.

Stadtpark Papenburg. Photo credit: Juliane Werner

More Top Articles on LAN

- 10 of the Most Common Mistakes People Make in Planting Design and How to Avoid Them

- Interested But Not Confident? – Know How to be Good at Hand Drawings

- Top 10 YouTube Tutorials for Technical Drawing

Regional Garden Show – More than a Framework

Using the benefits of a regional garden show, RMP landscape architects brought a wind of change into the city with a new garden and park culture. Visitors and residents now have the chance to admire flower shows, ships, and water elements incorporated with an urban flair. Paying attention to the historical structure and existing vegetation, the designers combined the vastness of lawns with compact structures of native trees and shrubs, resulting in interesting light and shadow effects. The implementing company (Landesgartenschau Papenburg 2014) saw in the garden show not only a framework; they went beyond classical structures and made the area attractive through landscape investments.

Stadtpark Papenburg. Photo credit: Juliane Werner

Recommended Reading

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

Stadtpark Papenburg As Part of Urban Marketing

In the economic development of a city, urban marketing is a strategic element. Marketing helps cities accomplish multiple objectives, such as developing tourism, attracting new companies, or consolidating technical infrastructure. But how can urban marketing benefit from landscape architecture? The city park in Papenburg is now a main element in tourism development, from which local companies can also profit and evolve. From a neighborhood perspective, residents now benefit from a newly designed park and can spend time in its direct proximity, which offers much more than a private garden.

Stadtpark Papenburg. Photo credit: Juliane Werner

Stadtpark Papenburg. Photo credit: Juliane Werner

Stadtpark Papenburg. Photo credit: Juliane Werner

The Right Time and Right Connections

Before deciding to use a regional garden show to improve the livability and urban climate, additional factors have to be taken into account. Besides the location, economic considerations, and political perspectives, the transformation has to be made in the right time with the right connections.

Stadtpark Papenburg. Photo credit: Juliane Werner

More Top Articles on LAN

- 10 of the Most Common Mistakes People Make in Planting Design and How to Avoid Them

- Interested But Not Confident? – Know How to be Good at Hand Drawings

- Top 10 YouTube Tutorials for Technical Drawing

Being part of a regional garden show means your project will profit from multiple benefits. In the case of Stadtpark Papenburg, bringing new details into the park but also paying attention to historical structures was almost a receipt for successful development. Being aware that landscape design within a regional garden show is a main element of urban marketing methods means creating different and multidimensional niches to cover the contrasting needs of residents, tourists, and developers.

Stadtpark Papenburg. Photo credit: Juliane Werner

Stadtpark Papenburg. Photo credit: Juliane Werner

Questions to Reflect Upon

Even if a regional garden show reveals many positive aspects, it is “just” a time-limited program of active transformation. But what remains after the events, shows, and temporal staging? Which are crucial aspects that have to been taken into consideration after such a program? How can a city sustain the positive transformations after a garden show ends?

Stadtpark Papenburg. Photo credit: Juliane Werner

Full Project Credits for Stadtpark Papenburg

Project: Stadtpark Papenburg Location: Papenburg, Germany Designers: RMP Stephan Lenzen Landschaftsarchitekten. (Thomas Brenning, Philip Haggeney, Chris Hoffmann, Inga Janßen, Thomas Kißmann, Jan Kückmann, Karsten Lindemann, Franziska Schmeiser, Katharina Thoma) Completion: 2014 Costs: 4.1 M Euro Area: 15 ha Client: Landesgartenschau Papenburg 2014 gemeinn. Durchführungsgesellschaft mbH Show on Google Maps

Recommended Reading

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

Article by Ruth Coman

New Neighborhood in Stockholm To Foster Sustainable Development

Royal Neighbour, by ADEPT and Mandawork, in Stockholm, Sweden. One might say that the first Global Environmental Conference was not Rio+20 in 1992, but The United Nations Conference on The Human Environment (UNCHE), which took place in 1972 in Stockholm. Although some people may disagree with this affirmation, there is no doubt that the UNCHE, whose main goal was to reduce human impact on the environment, was the first attempt at making society aware of the potential negative consequences of our existing development model on our living and to preserve the environment for coming generations. Since then, the city of Stockholm has focused on sustainable development alternatives and is still trying to maintain this reputation. Nowadays, according to the City of Stockholm, the Environment Program focuses on six key priorities: 1. Environmentally efficient transportation 2. Goods and buildings free of dangerous substances 3. Sustainable energy use 4. Sustainable use of land and water 5. Waste treatment with minimal environmental impact 6. A healthy indoor environment. As a consequence of this effort, the city of Stockholm leads the world in sustainable neighborhoods and boasts one of Europe’s largest urban development projects: Stockholm Royal Seaport or “Royal Neighbour”.

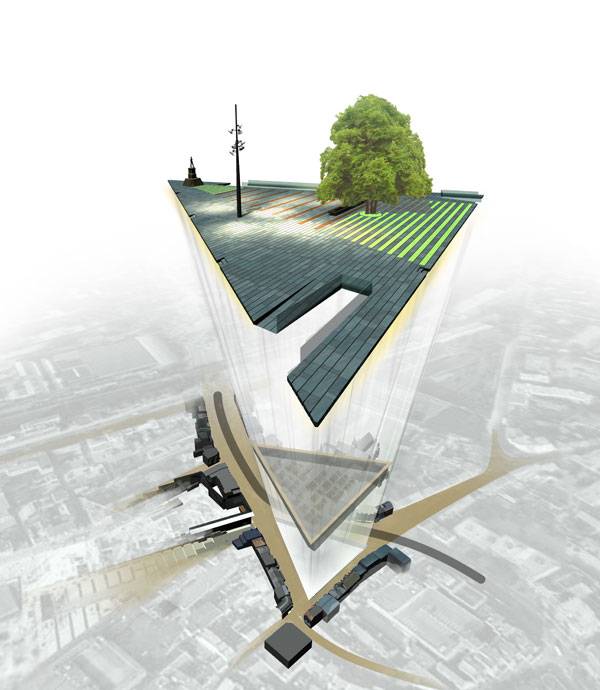

Masterplan of Royal Neighbour. Image courtesy of ADEPT

Royal Neighbour

Last May, the city of Stockholm disclosed the winners of a design competition for an urban development in the area of Stockholm’s Royal Seaport, formerly a gasworks area of about 236 hectares. ADEPT and the landscape studio Mandaworks designed the winning project, and both have been working closely with the city to develop the master plan for an 18-hectare area known as Kolkagem-Ropsten.

More Top Articles on LAN

- 10 of the Most Common Mistakes People Make in Planting Design and How to Avoid Them

- Interested But Not Confident? – Know How to be Good at Hand Drawings

- Top 10 YouTube Tutorials for Technical Drawing

Bringing 35,000 New Jobs

There are plans to build more than 12,000 new properties, bringing 35,000 new jobs and a new cultural area to the site. Moreover, the designers have created three new neighborhoods, each with its own unique architectural character brought to life by several architecture studios, including Herzog & de Meuron and Tham & Videgård Arkitekter, making sure the surroundings have a considerable variety of typologies and aesthetics. In March of this year, the design studio Tham & Videgård Arkitekter unveiled a plan to build four high-rise apartment blocks constructed from solid timber on an old harbor in Stockholm. The architects are planning to use only one material — Swedish pine — throughout the entire building structure.

Recommended Reading

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

Royal Neighbour. Image courtesy of ADEPT

34-story Skyscraper Entirely of Wood

In 2013, CF Moller unveiled plans to build a 34-story skyscraper entirely of wood, also in Stockholm, as a cheaper, easier, and more sustainable solution for housing. This novel approach, using renewable materials and deviating from the existing steel and concrete solution, illustrates the potential of including a variety of designers in the development of the Stockholm Royal Seaport area.

Royal Neighbour. Image courtesy of ADEPT

Royal Neighbour. Image courtesy of ADEPT

More Top Articles on LAN

- 10 of the Most Common Mistakes People Make in Planting Design and How to Avoid Them

- Interested But Not Confident? – Know How to be Good at Hand Drawings

- Top 10 YouTube Tutorials for Technical Drawing

Royal Neighbour. Image courtesy of ADEPT

You’ll Have to Wait Until 2030

Without a doubt, when we see a provoking and exciting project such as this one, it is more than natural to be anxious about its completion. However, the latest update regarding the project schedule confirms to have phase one starting in 2017. All the other remaining phases of construction are expected to be finished by 2030. In conclusion, when it comes to sustainability, it is great to see how far the city of Stockholm has been reaching since 1972. Certainly, it is a project worth following closely, and is an outstanding example of a sustainable project and a free lesson on why we should keep pushing ourselves to do better in the urban development realm and seek more environmentally conscious solutions no matter what.

Royal Neighbour. Image courtesy of ADEPT

Full Project Credits for Royal Neighbour

Project Name: Royal Neighbour Architects: ADEPT Landscape: Mandaworks Location: Stockholm, Sweden Total Area: 180000.0sqm Project Year: 2035 First phase of construction slated to begin in 2017 Client: Stockholm City Show on Google Maps

Recommended Reading

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

Article by Sarah Suassuna

How Wadi Al Azeiba Went from a Problem Site into a Success Story

Wadi Al Azeiba, by Atelier Jacqueline Osty & associés, in Muscat, Sultanate of Oman. Let’s be honest: You know you’ve walked past a vacant or rundown lot at some point in time. Maybe it was near your home, in your neighborhood, or by your school or workplace, but we have all seen a piece of land that is unkempt, neglected, or left for nature to take care of. Designed by Atelier Jacqueline Osty & associés, the Wadi Al Azeiba project is an interesting take on how to better utilize spaces we may otherwise find unappealing or vacant of design promise. A wadi, in some Arabic-speaking countries, is a term used to describe a gateway for water during storm events, not unlike a valley or ravine. The wadi channels water when during storms, but otherwise stays completely dry outside of the rainy seasons. Brush and weeds tend to overtake these areas, leaving them closed off for pedestrians as well as more vulnerable to being a collector of refuse. Inside this Article:

- Connecting Back to the Environment

- Planting at Wadi Al Azeiba

- The Pathways at Wadi Al Azeiba

- What If All Abandoned Lots Got a Makeover?

- Full Project Credits for Wadi Al Azeiba

- Recommended Reading

Wadi Al Azeiba. Image courtesy of Atelier Jacqueline Osty & associés

Wadi Al Azeiba

This wadi, located in the city of Muscat, is part of a city plan for new urban parks and planning strategies. The site passes through some of Muscat’s residential neighborhoods on its way toward the sea, as well as being just west of downtown and only a few miles from the airport. Because this wadi, like many others, runs through urban areas, when flooding events do occur, it can severely interfere with the city’s circulation and block off roadways.

More Top Articles on LAN

- 10 of the Most Common Mistakes People Make in Planting Design and How to Avoid Them

- Interested But Not Confident? – Know How to be Good at Hand Drawings

- Top 10 YouTube Tutorials for Technical Drawing

The placement of an urban park in this location has proved to be a smart one. The wadi is central to many hubs of activity that derive from residents, businesses, and even tourism. These different forms of activity make for a diverse use of the park by guests, in addition to adding value to the neighborhoods it borders. City planning models worldwide are all beginning to embrace the concept of urban parks as being vital to the success of any urban fabric.

Image courtesy of Atelier Jacqueline Osty & associés

Connecting Back to the Environment

Taking a closer look at this project, we can see that the designers played with inspiration from the mountainous backdrop and dry rivers and created a more modern interpretation. The mountains are symbolized through the use of concrete and grass to create terraced recreation areas that lead down to the bottom of the wadi, where the waterworks take place.

Recommended Reading

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

Wadi Al Azeiba. Image courtesy of Atelier Jacqueline Osty & associés.

Planting at Wadi Al Azeiba

The transition from the top of the park to the lower level is observable by planting style; you will see more structured and ornamental plantings at the top of the terraces, such as perfectly offset palms bordering pathways. The upper portion is also where many main pedestrian pathways run through the site. The plantings at the lower portion of the wadi are less formal and more natural, meant to be left as a native representation of how a wadi functions in nature, using more hearty and resilient vegetation.

More Top Articles on LAN

- 10 of the Most Common Mistakes People Make in Planting Design and How to Avoid Them

- Interested But Not Confident? – Know How to be Good at Hand Drawings

- Top 10 YouTube Tutorials for Technical Drawing

Wadi Al Azeiba. Image courtesy of Atelier Jacqueline Osty & associés.

Wadi Al Azeiba. Image courtesy of Atelier Jacqueline Osty & associés.

The Pathways at Wadi Al Azeiba

The linear quality of the site provided by the concrete paths and steps is broken up by the varied sizes of rock used to line the bed of the wadi, resembling a dry riverbed. Another key feature of the design of this site is the implied uses it creates. Being located in an urban area makes it difficult to avoid the dominance of vehicles, but Atelier Jacqueline Osty & associés designed the Wadi Al Azaiba so that recreation such as walking and biking are at the forefront, encouraging people to utilize other forms of travel or to simply take time to walk around and enjoy the place.

What If All Abandoned Lots Got a Makeover?

The city of Muscat took a bold first step toward improving the connection of it residents and visitors with the environment and to further connect them to the place they call home. It’s easy to forget about what makes a place memorable and functional, especially something the entire community can enjoy. When we take a macroscopic look at a city and what could improve its quality and function, those abandoned lots and forgotten alleyways are hidden gems that can reconnect the city and its inhabitants.

Wadi Al Azeiba. Image courtesy of Atelier Jacqueline Osty & associés.

Wadi Al Azeiba. Image courtesy of Atelier Jacqueline Osty & associés.

Wadi Al Azeiba. Image courtesy of Atelier Jacqueline Osty & associés.

Wadi Al Azeiba. Image courtesy of Atelier Jacqueline Osty & associés.

Wadi Al Azeiba. Image courtesy of Atelier Jacqueline Osty & associés.

Full Project Credits for Wadi Al Azeiba

Project Name: Wadi Al Azeiba Team: Landscape architect: Atelier Jacqueline Osty & associés (Jacqueline Osty, Maythinie Eludut, Adrien Thomas, Gaylord Le Goaziou) with Concepto, lighting designer, COWI Engineer company Start of Construction: Phase 1: 2011-2012, Phase 2: TBD Client: Municipality of Muscat Location: Muscat, Sultanate of Oman Planning: Phase 1: design phase: 2010, construction: 2011-2012, Phase 2: design phase: 2014, Area: Phase 1: 2 hectares, Phase 2: 13 hectares Show on Google Maps

Recommended Reading

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

Article by Megan Criss

Zamet Centre is so Much More Than Just a Sports Center and People Love it

Zamet Centre, by 3LHD, in B. Vidas Street, Zamet, Rijeka, Croatia. Have you ever played handball? I did, but only as a child. So when I discovered that the project I am writing about played host to a handball championship, I was a bit surprised. I wondered, is handball the Croatian national sport? And then my mind went to the Olympic games and the large number of buildings that lose their sense after the event for which they were built is done, and I started to become distressed. But the more I read about Croatia’s Zamet Centre, the more astonished I became. When architecture speaks for itself and when it works — as it does in this case — it integrates into the environment in a very sharp way, satisfying many demands at once with a strategic multi-functionality. But let’s start from the very beginning: The city of Rijeka, nestled between the Adriatic Sea and the mountains, was asked to create a suitable environment for the world championship of handball in 2009. The Croatian office of 3LHD won the private competition for the sport and community center in Zamet, one of Rijeka’s quarters.

Zamet Centre. Photo credit: Damir Fabijanic

Zamet Centre

What happens when a strongly characterized building is added to a primarily residential neighborhood is that it becomes the very core of neighborhood life. In Zamet, the sports complex insinuated itself even more by providing a pedestrian path linking the neighborhood north to south, passing through the civic hub with its plaza, shops, local community offices, and civic center. The designers achieved their aim of giving a recreational aspect to the environment while at the same time creating other useful public spaces, including a public square, shops, a library, public offices, and underground parking.

More Top Articles on LAN

- 10 of the Most Common Mistakes People Make in Planting Design and How to Avoid Them

- Interested But Not Confident? – Know How to be Good at Hand Drawings

- Top 10 YouTube Tutorials for Technical Drawing

Zamet Centre. Photo credit: Damir Fabijanic

Generating a New Hub of Activity

The modern nature of the project gives a strong personality to a place that had lacked a real gathering place, links, and services. Moreover, it provides a welcoming space to play sports, attend concerts, and host all kinds of events. How can a square or a big building be in dialogue with the surrounding landscape without seeming to have been thrown in at random? 3LHD, winners of numerous awards for this project, were faced with the challenge of designing within a matrix that was mainly residential spread, dotted with a few isolated residential towers.

Zamet Centre. Photo credit: Damir Fabijanic

Where Does the Landscape End and the Building Begin

The main building was covered with stripes, running from north to south along the main building and the small shops and offices collateral to the square. These “ribbons” are the main piece of the project, taking on different turns; they play the game of turning roofing elements into flooring elements, staircases, paths, and green roof covers.

Zamet Centre. Photo credit: Damir Fabijanic

Working With the Slope to Create the Space

The square plays between gradients and the natural and the artificial, and determines the zero plane of connection among the road to the south, the commercial activities, the sports hall, and the connections to the school and the park situated to the north. The intervention is exceptional in its kind; it does not distort the place, but completes it. The skilled group of architects precisely transformed what was once the biggest problem of the place –the slope — into the main force element.

Zamet Centre. Photo credit: Damir Fabijanic

Zamet Centre. Photo credit: Domagoj Blazevic

Zamet Centre. Photo credit: Domagoj Blazevic

Zamet Centre. Photo credit: Miljenko Bernfest

Full Project Credits for Zamet Centre

Project Name: Zamet Centre Program: Public, cultural, business, sport Location: B. Vidas Street, Zamet, Rijeka, Croatia Architect: 3LHD Project Years: 2004-2008 Construction: December 2007-October 2009 Geolocation: 45-20-39 N, 14-24-0 E Site Area: 12.289 m2 Size: 16.830 m2 Volume: 88.075 m2 Footprint: 4.724 m2 Budget: 20 mil € Client: Grad Rijeka / Rijeka Sport d.o.o. Main Contractor: GP Krk

Recommended Reading

- Landscape Architecture: An Introduction by Robert Holden

- Landscape Architecture, Fifth Edition: A Manual of Environmental Planning and Design by Barry Starke

Article by Valentina Ferrari