On August 11, 2017 in Charlottesville, VA, amidst signs of hatred and spewed words of bigotry, violence erupted as white nationalists clashed with counterprotesters, leading to one person killed and 19 injured. The aftermath of the Charlottesville riot, spurred by the city’s plans to remove symbols of its Confederate past, reignited the debate over what should happen with Confederate landmarks in cities across the country.

On the Land8x8 Lightning Talks stage, Harriett Jameson Brooks, landscape designer at MVLA, shared her deep connection with Charlottesville, and how she turned to her profession as she grappled with this blatant display of hate and racial tension that did not match how she saw the progressive, democratic city.

Since the upheaval in Charlottesville, a movement to remove Confederate memorials from public property has gathered steam. While many argue for the preservation of such memorials as a reminder of the country’s history, others regard them as glorification of a shameful time in American history. Harriett understands the desire to preserve history – if only to impart important lessons about the ugliness of the past – however, she confesses that the desire to hold on to tradition is “also a way of justifying our inertia and our hesitancy of picking the past over the future, choosing fear over courage and possibility.”

Image: Harriett Jameson Brooks

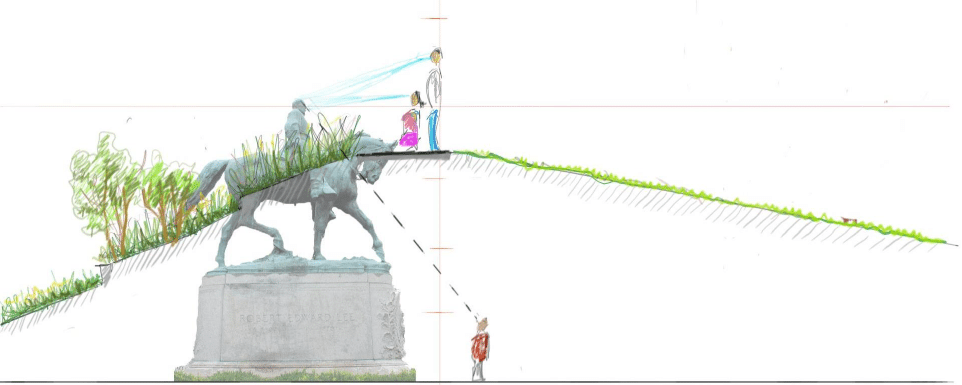

“I realized that if there are 1,500 symbols of the Confederacy on public property in the U.S., then there are 1,500 public places in our country that need to be redesigned, reimagined, and reconciled.”

Today there are 1,500 symbols of the Confederacy on publicly supported land in the U.S., including monuments, schools, parks, and roads. While many would see this as a barrier, Harriett considers it an opportunity. “It shook me as a landscape architect.” Harriett exclaims, “I realized that if there are 1,500 symbols of the Confederacy on public property in the U.S., then there are 1,500 public places in our country that need to be redesigned, reimagined, and reconciled.” With a desire to reclaim public space in the South and bring together communities, Harriett formed the Common Ground Collaborative. Through this initiative, she intends to work with communities to create public spaces that reflect their collective values.

While landscape architects are not typically at the forefront of these type of social issues, Harriett urges the importance of joining, if not leading, the conversation. In an effort to confront these types of complicated challenges and push past the existing limitations of the profession, Harriett pursued the LAF Fellowship for Leadership and Innovation. Designed to empower leaders and innovators in the profession, Harriett states that “each of this year’s fellows is finding a way to push back, to expand what it means to be a landscape architect, what types of problems we take on, and why we do the work that we do.” As one of four recipients of the 2017 LAF Fellowship, Harriett has spent the past year exploring ideas such as this that push landscape architects into the conversation and catalyze positive change.

In closing, Harriett proclaims, “I see the world that landscape architects can create when open ourselves to what is deeply personal, when we explore our periphery, and when we take hold of the future waiting to emerge.”

—

This video was filmed on September 28th, 2017 at ASLA’s Center for Landscape Architecture in Washington, DC as part of the Land8x8 Lighting Talks sponsored by Anova Furnishings.

![Deep Collaboration: Ecology, Research, Design [Video]](https://land8.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/stephanie-carlisle-224x150.png)

![Transforming Tysons [Video]](https://land8.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/sp-land8x8-224x150.png)